Steve Gerber: Hard Labor

By Darren Schroeder

DC Comics has recently initiated a group of new comics collected

under the imprint DC Focus. The stated intention of the line is to

look at the concept of super powers from a new angle. Steve Gerber,

well known for his groundbreaking work on Man-Thing, Howard

the Duck and Void Indigo is the writer of Hard

Time, launched un the DC Focus banner. It follows the youthful

Ethan, as he finds himself in prison for his part in a high school

shooting. Steve took time off from his work on the book to chat about

the book.

Darren Schroeder: How did the idea for the Hard

Time scenario develop?

Darren Schroeder: How did the idea for the Hard

Time scenario develop?

Steve Gerber: This answer is a multi-parter. Bear with me.

Part One. High school shootings, the kids who commit them, and the

motivation for them have interested me since Columbine. I was one of

those kids who grew up as an outsider. I was bullied. I was the butt

of jokes. I was the fat kid. I was the comic book geek. I was the

last kid picked for every team in gym. In other words, I was just the

sort of kid who, today, might be tempted to seek an extreme solution

to his angst and alienation. To put it a little too glibly, I felt

that some high school shooters were, getting a bad rap from the

media. This is not to say that the crimes weren't reprehensible, just

that the public might not be getting all sides of the story. That

thought had been percolating in the back of my mind for a while.

Part Two. At the San Diego convention of 2002, former DC editor Andy

Helfer approached me about contributing to a new line of comics he

was trying to put together. Andy's idea was to do stories about

people with super-powers, as opposed to super-heroes. Andy also

wanted to challenge the single most basic assumption of all

super-hero comics -- that when a person acquires super-abilities, he

or she is irresistibly compelled to put on a costume and become

either a hero or villain. Andy wanted to treat the powers like any

other human talent: athletic prowess, musical genius, mathematical

brilliance, and so on. Those talents can and do lead gifted persons

down any number of different, sometimes very twisted paths. Why

wouldn't the same be true of someone who discovers he can change the

course of mighty rivers?

All of which sounds simple enough, but is in fact a very radical

premise for a line of books.

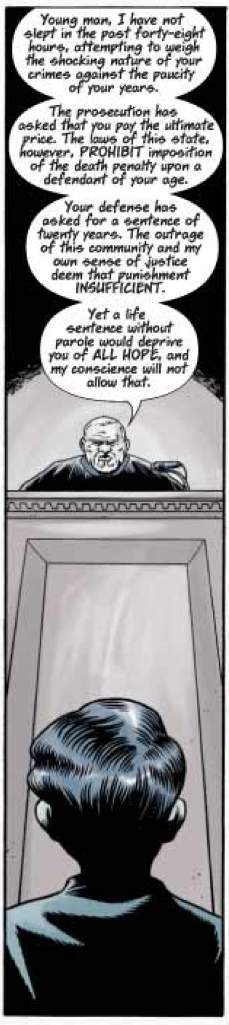

Part Three. A couple of weeks later, back at home, I caught a news

story about the trial of one high school shooter in California. He

was fifteen at the time of the incident, but due to the nature of the

crimes, he had been tried as an adult. The sentence handed down was

50 years to life. I couldn't believe what I was hearing. A judge, a

prosecutor, and twelve people in a jury box were that

convinced that a fifteen-year-old offender was beyond all hope of

redemption and rehabilitation.

That solidified the Hard Time premise for me -- a kid who

participates in a high school massacre, gets tried as an adult, and

is sentenced to spend most of his life in prison.

DS: The page of issue one that deals with TV talk shows hits

some targets on both sides of the issue of youth crime. What was it

that kept you from breaking the law as a kid?

SG: I had a conscience, which was shaped by the examples set

by my parents and, uh, Superman. I know that sounds unbearably corny,

but it's the truth. The irony, of course, is that that conscience

also led me and countless others of my generation to defy the law

later on, over matters like the Vietnam War and civil rights.

DS: "Tougher penalties = less crime" Is that a sensible

equation?

SG: Absolutely. That's why Texas is now crime-free.

DS: Fifty years in the big house. Did you do any research on

how long-term prisoners cope with that sort of sentence?

SG: I did a lot of research on prisons and prisoners in

general - Department of Corrections websites from all over the

country, prisoner websites, non-fiction books, documentary films, a

couple of novels, and, of course, the indelible imprint of countless

movies and television shows - There's an entire inmate subculture

with customs and norms of behavior completely separate from, and

sometimes totally at odds with, the society most of us inhabit. Once

those gates slam behind you, it's as if you've stepped onto the

Bizarro world.

SG: I did a lot of research on prisons and prisoners in

general - Department of Corrections websites from all over the

country, prisoner websites, non-fiction books, documentary films, a

couple of novels, and, of course, the indelible imprint of countless

movies and television shows - There's an entire inmate subculture

with customs and norms of behavior completely separate from, and

sometimes totally at odds with, the society most of us inhabit. Once

those gates slam behind you, it's as if you've stepped onto the

Bizarro world.

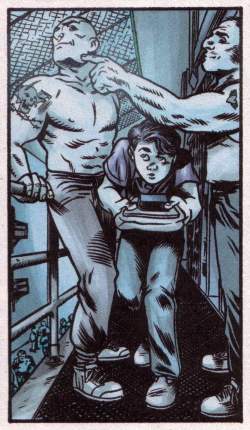

I also needed to know how a prison itself functions. There are a

million questions that arise as soon as you start to write a series

like this, and they all have to be answered believably. How much

freedom of movement do inmates have within the prison? Do have any

privacy at all? What are the lines of communication among the

inmates, and between inmates and authority? What kind of weapons do

the guards carry? How much do inmates get paid for whatever work they

perform in prison shops? What sort of food do they serve in the

cafeteria?

And, yes, there was the overarching question of inmate psychology.

Can human beings really adapt to living in hell? Can they come to

prefer it? After a time, do they fear the unknown world outside more

than the everyday brutality with which they're familiar? There's no

single answer to those questions. Every prisoner is different. Each

individual adapts, or doesn't, in his own way.

DS: Lots of prison narratives seem to construct the prison

population as mainly a bunch of good sorts with just a few bad eggs

thrown in for plot purposes. Is this just a function of telling

stories - readers need to like most of the characters - or is there

just no correlation between being a convicted criminal and being

un-likeable?

SG: Good question. Ted Bundy was a charmer. Jeffery Dahmer

lured sixteen victims into his apartment and, ultimately, his

refrigerator. And those are the serial killers. Imagine how

personable a successful confidence man has to be.

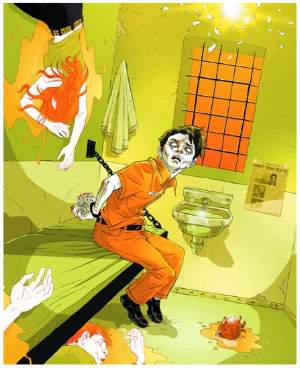

We've taken pains to portray the characters in Hard Time as

multidimensional. Some of them are oddly likeable. On the other hand,

almost all of the inmates are capable of committing heinous acts of

violence with only minimal provocation. We've tried to keep readers

mindful of that.

DS: How many issues do you have plotted?

SG: The first seven scripts are written. I've started on the

eighth. DC has given us the green light for at least twelve

issues.

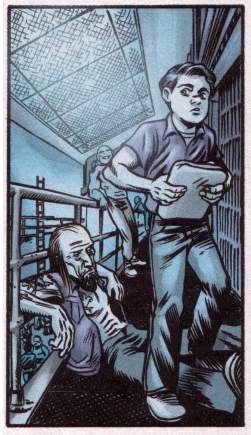

DS: The artwork I've seen has quite a low-key, grim look to

it. Are you pleased with that?

SG: Very much so. Brian Hurtt's artwork has captured the tone

of this series just about perfectly. There's a sense of foreboding,

of quiet menace, in almost every panel. It's in the faces and body

language of the characters, and the shadows of the prison. And the

longer you look at the art, the more that understated darkness creeps

up on you. It's very powerful work.

Equally remarkable is the fact that Brian's storytelling is as crisp

and clear as that of any artist I've worked with. He's managed to

combine a kind of bleak visual poetry with a very mainstream, very

direct narrative style. The result is something like a Hitchcock film

-- apparently straightforward on one level, but deeply disturbing on

another.

DS: Are we going to learn anything about the source of Ethan's

powers?

SG: Over time, yes, but not right away. The powers have been

latent in him, possibly since birth. We've seen them surface under

conditions of extreme stress. There may be other triggers, as

well.

DS: From this side of the globe (New Zealand) violence in high schools seems to be a big issue in the US, Were you worried that your look at it in Issue one might worry DC?

SG: At first, there was some nervousness about the premise, but in a rare display of good sense on everyone's part, we dealt with it before I began writing the first script. DC had an outline of the first six issues, so they knew what was coming and approved it.

More than "approved", really. Dan Didio, DC's VP-Editorial, and Joan Hilty, who edits the book, have staunchly supported Hard Time from the start. This is one of the few occasions in my career -- which spans more than thirty years now -- that I've felt a publisher has been completely supportive of my efforts on a new series.

DS:

DC versus Marvel, what differences have you noticed in dealing with

them recently from a creatorıs viewpoint?

DS:

DC versus Marvel, what differences have you noticed in dealing with

them recently from a creatorıs viewpoint?SG: Well, it's highly unlikely I could ever have done Hard Time at Marvel, even if I'd been willing to sell all the rights. Creatively, Marvel pretty much confines itself to makeovers of the company's extant trademarks. DC is more willing to take risks with original properties and has been much more flexible on the business side, as well.

DS: Do they get the rewards deserved for that risk-taking?

SG: If every risk paid off, it wouldn't be a risk, but yes, I think DC has reaped some substantial rewards. Some of their best-selling trade paperbacks are original properties -- Sandman, Watchmen, Preacher, Transmetropolitan. Those books have been earning money for their creators and for the company for years now, and they'll continue to. I'm sure there've been film and TV deals, too, on DC's newer properties.

DS: Jocks versus Geeks, who do you think needs to change their ways?

SG: Is there really any question? Let this be a warning to every brutish, sadistic geek in the audience. Stop picking on those poor defenseless jocks. Stop stealing their women. Show some compassion, for once. Or there will be hell to pay.

DS: From what we see in the first issue it seems like Ethan is going to have to grow up fast if he is to survive prison life, but the script for issue two suggests another side to him, his seeming pleasure in taking revenge. It comes across as quite a calculated move. Will we see more of this aspect of his character as the story developments?

SG: I don't want to reveal too much of the story, but -- in the incident you're referring to, the use of his power is "calculated" on an unconscious level. Ethan's power is at work while he's asleep and without his knowing it. That becomes evident in the third issue.

We're taking a somewhat unusual approach to the writing of this book. Characters and plot elements are being revealed over time. We don't spell everything out right away, or in full. Hard Time isn't a book for readers who lack patience or don't like surprises.

DS: I'm assuming you've enjoyed writing comics in the past, so is it still fun writing them now?

SG: Sometimes. I certainly enjoy working on Hard Time. It's the first opportunity I've had in a long while to do an open-ended series, to let characters and plotlines develop at their own pace, over time. And these characters themselves are fascinating. They surprise me frequently, if you know what I mean -- they sometimes refuse to behave the way I'd like them to behave. They've taken on a life of their own. That's fun.

DS: In issue one you show the TV commentators' reactions to the issues in a stream of rather shallow sound bites. Are mainstream TV shows willing, or even able to do more?

SG: "Willing", no. In America, we go for the ratings, social responsibility and nuance be damned. "Able" is a more difficult question to answer. I'm sure there are some very intelligent people involved even in the production of the afternoon talk shows. Would they be allowed -- by the syndicators, the networks, or ultimately even the viewers -- to explore issues in greater depth? I doubt it. One way or another, they'd be penalized.

DS: Your scripts stipulate a lot about the layout of the

pages. Do you do rough sketches of theses while you are working on the

stories?

DS: Your scripts stipulate a lot about the layout of the

pages. Do you do rough sketches of theses while you are working on the

stories?SG: Very rarely, and even then just stick figures. Usually, I just see the scene in my head and try to describe it as best I can for the artist. I've never been able to draw.

By the way, the art descriptions aren't really "stipulations". Brian makes changes in the staging when necessary, and he knows I trust his judgment.

While we're on the subject of scripts, I need to credit Mary Skrenes for her extremely valuable behind-the-scenes contribution to the book. This is the first chance Mary and I have had to work together since we created and wrote Omega the Unknown for Marvel a few decades back. She's been an enormous help on Hard Time. (Ethan Harrow isn't a direct descendant of James-Michael Starling, but they do have traits in common -- and now you know why.)

DS: I see the script of issue 1 is dated March/April 2003. Is that sort of gap between writing and publishing the norm with comic publishing?

SG: No. It's generally more like four to six months, depending on the publisher and the nature of the project. In this particular case we had a longer lead time, because Brian Hurtt had other commitments and wasn't able to start work on the book until about September of 2003.

DS: How long had you been working on the idea before then?

SG: I submitted the initial presentation in September, 2002. DC took a little while to decide whether they wanted to do the book. Then, we had to negotiate a contract. And then, I took a very long time to get the six-issue outline done. That was finished and approved by DC in February, 2003.

DS:

What's your understanding of the theme for the DC Focus line of

comics?

DS:

What's your understanding of the theme for the DC Focus line of

comics?SG: As I mentioned earlier, the Focus titles are series about people with super-powers, as opposed to super-heroes. They're set in the real world, rather than a comic book universe. There are no super-hero clubs to join. There are no costumed villains, as far as I know. The stories, ideally, grow out of the characters, rather than simple hero-villain match-ups.

By the way, I've noticed on the net that some people assume the Focus books constitute a new "universe". That's not the case. Focus is simply an imprint, a grouping like Vertigo, not a universe. Each of the books is completely free-standing, and everyone's intention, at least for now, is to keep them that way.

DS: I once got a letter from a convicted thief in prison asking for some free comics. I send him some back but pointed out that trying to get something for nothing seemed to be a habit with him. Have you received any fan mail from prisoners yet?

SG: Not yet. It'll be interesting to see what they have to say.

DS:

What poster would you put up on the wall of your prison cell?

DS:

What poster would you put up on the wall of your prison cell?SG: Back in college, I had this very strange violet and purple psychedelic poster of Rasputin. I doubt that any copies exist anymore, but that would be my first choice. Alternatively, various Helmut Newton photographs might work.

DS: Apart from Hard Time, what have you been working on recently?

SG: Actually, Hard Time has been consuming most of my energy.

DS: My heightened interviewer senses are tingling - is there anything else you'd like comment on?

SG: There is one thing, yeah. A couple of reviewers have complained that we loaded the first issue of Hard Time against Ethan, railroading him through court in a way that made the American justice system look bad and Ethan appear too sympathetic.

Those reviewers need to do a little more research.

Under the law, Ethan actually was guilty of every single charge brought against him, including felony murder, even though his gun was never fired. Simply by participating in a crime that resulted in someone's death, Ethan was eligible to be prosecuted for murder -- not as an accessory to murder, but as a murderer. Throw in a zealous prosecutor and an angry jury pool, and Ethan's 50-year sentence doesn't seem even a little outrageous or contrived. In fact, sentences like Ethan's are handed down all the time in the U.S., even to 15-year-old offenders. It's not even unusual.

DS:My thanks to Steve for his time. Hard Time #3 should be the stores in the next few weeks.

Check out Steve's website: http://www.stevegerber.com