Shane Simmons chats with SBC

Posted: Wednesday, April 5, 2000

By: Darren Schroeder

More than a few years ago I got sent some mini comics from Canada, amongst them was the hilarious Angry Comics. At the time I commented "On those cold nights in the Canadian wilderness the lone Mountie breaks the stillness of the night with his laughter as he lays under the stars reading his prized collection of Shane Simmons works." In 1994 we traded some comics then lost touch. During some web searches I was pleased to see that others shared my view of his work, with such comments as:

Shane Simmons is the critically-acclaimed creator of Longshot Comics and Money Talks (Slave Labour Graphics), two comic book series that have stretched the limits of what defines the modern comic art form. A ten-year veteran of the comics industry, his stories have appeared in anthologies and magazines around the world, including Formaline, The Slab Collection, and Tower Records' in-store publication, Classical Pulse. From Concept. Through some more searching I managed to track Shane down and renew our comic exchange, though I fear that Shane is getting the raw end of the deal. I decided to take the opportunity to ask him if he would be willing to be the subject of an interview. While he agreed I wasn't to hear back from him for a while so was getting a bit concerned, then I recently got a reply:

Through some more searching I managed to track Shane down and renew our comic exchange, though I fear that Shane is getting the raw end of the deal. I decided to take the opportunity to ask him if he would be willing to be the subject of an interview. While he agreed I wasn't to hear back from him for a while so was getting a bit concerned, then I recently got a reply:

My gravest apologies for taking so long to answer this first batch of questions. Things got a bit crazy here. One of the more interesting upsets was the fire in my building that had me escaping into three feet of snow wearing only my bath robe and slippers. This escapade got my picture in a local paper. Proud moment for me.

I'm glad he made it safe and sound, so before anything else happens we will start the interview.

Darren Schroeder: What is your full name?

Shane Simmons: I'll admit to having an alternate first name, but that's it. Shane Simmons is my real name, but by parents decided to slap me with a horrific middle name, and then further confound matters by affixing it to the front because "it sounded better there." I never go by it, except when dealing with bureaucrats like doctors and tax men who only look at the name on the medicare or social insurance card. Everyone else has just called me "Shane" my whole life, but this dark secret name has caused me no end of inconvenience.

DS: Age?

SS: I'll be thirty-two in July. It's taken me these two years to recover from turning thirty. Oh my God! I'm in my thirties! I'm aging! Ahhhhhhhrrg! I . . . I . . . I'm sorry. I thought I was past all that.

DS: Were comics a big part of your childhood or did you discover them at a later stage?

SS: I bought my first comic book when I was six years old, back when they were twenty-five cents an issue. I gave them up about six years later when they were closing in on a dollar an issue. I figured the industry was about to collapse because no one would ever pay a whole buck for a comic book.

For my comics fix, I started to concentrate on newspaper strips and paperback collections of those strips. In the end, though, I preferred my comics to have a strong ongoing narrative. Few daily strips ever attempted that. Mostly they were gag-of-the-day, with only a couple of exceptions standing out.

I rediscovered comic books in the mid-eighties when I friend loaned me a pile of new-wave titles like Watchmen and Dark Knight. I obsessively read anything I considered noteworthy, slipping more and more towards the off-beat, the alternative, the underground. It wasn't long before I'd completely abandoned the mainstream. I preferred to focus on individual artists who were pushing the envelope -- the big publishers stopped doing that just after I got back into comics. Now I have a list of writers or writer/artists who I follow regularly, whatever their project or publisher.

DS: Care to name them?

SS: Admittedly, I'm probably missing a few or more examples of their recent output, but generally I keep an eye out for stuff by: Dave Sim, Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, Matt Feazell, Sean Bieri, Dan Clowes, Chester Brown, Seth, Evan Dorkin, Roberta Gregory, Joe Matt, Peter Bagge, and maybe some others I'm forgetting here. I won't say that I think all their stuff is gold. Some of them (you decide which) have been in a slump for years now, but I'm loyal enough to keep coming back for more. You never know when one of them might do something really interesting.

DS: Were you one of those kids who draw lots of pictures while in school and become the class artist?

SS: That was me. I drew all through school, and learned more from the doodles in the margins of my notebooks than from my actual notes. These drawings would get passed around among my friends whenever the teacher got particularly boring. I ended up doing some short- lived strip work for school newspapers in high school and college. But there was editorial conflict with almost every strip, so I just started doing pages for myself.

DS: What was the first comic you published yourself and how did that come about?

SS: The pages I was drawing in the late eighties were semi-autobiographical, using myself and my friends as characters. Sometimes they would relate a skewed version of a real anecdote, other times they would be pure fiction. I'd bring them to parties and we'd pass them around for a laugh. Eventually I had a folder full of them and decided to start collecting them in minicomic form. That's how Angry Comics started. After a few issues, I had run out of old material and had to start coming up with new stuff. They were selling briskly in a number of Montreal shops, so that kept me interested. Within a few years I had put out thirteen issues of Angry Comics and a handful of other titles.

DS: Did you ever go out with a girl just because she had access to a photocopier? SS: No, but I've certainly cultivated friendships with people who had photocopier access -- particularly during the initial printing of the Longshot Comics minicomic. This was an eighty-page booklet I was selling for a buck-a-piece because I figured no one would ever pay more than a dollar for a story about dots. Getting free photocopies for the interiors was my means of keeping production costs down. Unfortunately, my sources for free copies dried up and I had to take it to a printer every couple of weeks to restock. In the end, the minicomic edition sold around eight hundred copies, but it became less and less profitable as time went by. By the last few printings, I'd raised the price to two dollars, but I was still having trouble keeping up with orders. It was time to take the project to a real publisher.

SS: No, but I've certainly cultivated friendships with people who had photocopier access -- particularly during the initial printing of the Longshot Comics minicomic. This was an eighty-page booklet I was selling for a buck-a-piece because I figured no one would ever pay more than a dollar for a story about dots. Getting free photocopies for the interiors was my means of keeping production costs down. Unfortunately, my sources for free copies dried up and I had to take it to a printer every couple of weeks to restock. In the end, the minicomic edition sold around eight hundred copies, but it became less and less profitable as time went by. By the last few printings, I'd raised the price to two dollars, but I was still having trouble keeping up with orders. It was time to take the project to a real publisher.

DS: Was art an important part of your education?

SS: Certainly not my formal education. I count it as one of those useful things I taught myself. Pretty much everything I know today I learned outside of school. I was always a good student, but beyond basic literacy and basic math, two decades of schooling offered me little more than daycare.

DS: What materials and equipment do you use when drawing your comics?

SS: No precision pens and brushes on quality paper for me. I'm at sea when other artists start talking about that stuff. I only use a variety of black felt tip pens of varying point size on standard white paper -- the kind you'd find in any photocopier. Computers do a lot of the legwork for titles like Money Talks and Longshot Comics. PageMaker is my software of choice in these cases.

DS: How did you manage to keep going while you were in the middle of doing all those panels in the Eyestrain comics?

SS: For the first one it wasn't so bad. When I did the minicomic, it was fresh and reasonably interesting for me because it was such an experiment. For the regular-sized edition, it was just a matter of reformatting my original computer files and redrawing all the dots and lines -- tedious, but not a big deal. The worst part was having mono at the time. It was the second Longshot that kicked the shit out of me, though. I did all the art under a much stricter deadline, and it was just day after day of tiny panels and tinier dots. I started playing music that had a sort of kinetic energy to it to push me on. The soundtrack to Koyaanisqatsi figured heavily. By the time the project was done, I'd gone a bit loopy. Normally I'm a very level guy, but Longshot Two took me closer to the edge of sanity than I've ever been. Or maybe it was Philip Glass.

DS: With Money Talks, did you find it easier or harder to use the cut-up bank notes for characters instead of drawing them yourself?

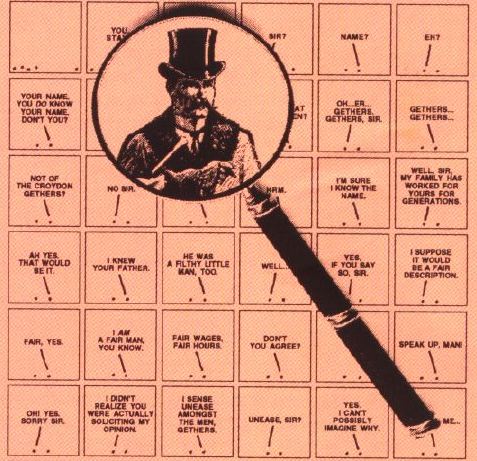

SS: Well certainly I could never have hoped to draw those great bank note figures myself panel after panel. But I didn't cut and paste them either. Few people realize they were actually computer scans, meticulously edited by me in a cheap bit of art software. There were four files for every character, and I would just drop the appropriate one into my layout and resize him as need be. The rest of the art I would hand draw after the page came off the printer. Making these files took an awfully long time, but I figured they would pay off in the long run more than cutting and pasting. They might have too, if the series had lasted twenty-five issues as I intended. I don't know if I saved myself much work for only five issues.

SS: Well certainly I could never have hoped to draw those great bank note figures myself panel after panel. But I didn't cut and paste them either. Few people realize they were actually computer scans, meticulously edited by me in a cheap bit of art software. There were four files for every character, and I would just drop the appropriate one into my layout and resize him as need be. The rest of the art I would hand draw after the page came off the printer. Making these files took an awfully long time, but I figured they would pay off in the long run more than cutting and pasting. They might have too, if the series had lasted twenty-five issues as I intended. I don't know if I saved myself much work for only five issues.DS: I've always found it hard to get shops to stock comics that I have been trying to get in front of people, how did you deal with this in the Angry Comics days?

SS: Montreal already had a good number of stores supporting small press comics before I ever came along, so I knew which ones would be receptive to taking copies on consignment. Once Angry Comics started outselling a lot of their regular titles, it was even easier to find shelf space for them. Sometimes I'd exploit personal relationships to infiltrate new stores that I thought might be a good market for me. But there were also plenty of ultra mainstream outlets I never bothered with at all. It's mostly a matter of knowing your local marketplace. Forging friendships with cashiers is always a good move. If they like you and your work, they'll pass on a recommendation to regular customers.

DS: How did the "real publishers" react to your material?

DS: How did the "real publishers" react to your material?SS: Apparently the guys at Slave Labor had already heard of the Longshot minicomic, so when it showed up on their desk it wasn't a big shock. I had tried taking it to Kitchen Sink just before and got the standard "not our thing" form letter. But landing an offbeat project like Longshot Comics at the second door I went knocking on is pretty good. I've had other projects that never found a home anywhere. Strangely, it was probably the fact that Longshot was SO different and SO unusual that it grabbed publisher interest. Since then, I've had other publishers come to me looking for the foreign language rights. The German edition came out last fall.

As for Money Talks, that was an easy sale at Slave Labor since I already had a relationship with them. It was only the lack of public response that killed it after five issues. The people who read it generally liked it the way they liked Longshot, but felt they weren't getting the same bang for their buck. Oh well, not every comic can carry 3,840 panels of material.

DS: Were you happy with your experiences when others were publishing your work?

SS: I know there are lots of publisher horror stories that helped start the whole self-publishing boom, but I've never had a bad experience with anyone who's printed my work.

The worst story I can share dates back to that same period of time when I had mono. I was lying in bed, half dead, when I got a call from a guy who wanted to reprint an Angry Comics story called "The All-Crime Newlywed Game." This was a parody of the old Newlywed gameshow with Bob Eubanks. In my version, the featured couples were sex-slayers Paul Bernardo and Karla Homolka, penis slicers Lorena and John Wayne Bobbitt, figure-skater bashers Tonya Harding and Jeff Gillooly, and finally Joey and Mary Jo Buttafuoco. This guy really liked the story, but he had never heard of the Buttafuocos before. He wanted me to come up with a replacement couple and redraw and rewrite all of their panels. So there I was, a blazing fever, a throat of razors, an enlarged liver, and a real serious desire to fall into a coma, prodding this guy's memory -- "You know, Joey and Mary Jo Buttafuoco. The Long Island Lolita case. Amy Fisher." Nothing. This guy must have been living under a rock because it was still on TV every day. Joey Buttafuoco was the cornerstone of every talk show host's monologue. The story was bigger than the Kennedy assassination. Either of them.

Finally I just told him I'd get back to him once I was feeling better. Hanging up, I made a mental note to remember to forget to ever call him back. When it comes to comics, I'm really not interested in editorial input. I get enough of that shit screenwriting, so I might as well keep my comics pure.

DS: I've noted from my research on the web that you have an interest in aviation, how did that come about?

DS: I've noted from my research on the web that you have an interest in aviation, how did that come about?SS: Specifically I fancy WWI aviation. It's always been an interest of mine, even as a kid, and I don't really know why. It probably has something to do with my dad dragging me to see The Great Waldo Pepper when I was seven. Soon after I was buying any Enemy Ace comics I could get my hands on. I liked those weird old planes with two, even three wings. As an adult I started to read books on the subject just to satisfy my curiosity about the actual facts behind the legends.

Today I'm what I would call an amateur expert of some small note. I've written a few magazine articles on the topic, as well as a feature screenplay that continues to bounce around in development. I also enjoy reading all about air crashes and the investigations of the National Transportation Safety Board. That ties in better with my morbid fascination/fear of flying. I hate leaving the ground, I despise travelling at 30,000 feet, but I always ask for a window seat so I can catch the view.

DS: You've become involved in writing for TV and films, what shows/films have you written?

SS: This has become my day job. Lord knows, few people can make money writing comics. Mostly I've written for youth-oriented TV -- shows like Radio Active, Student Bodies, Back to Sherwood. There's a glut of kid productions in Montreal. A lot of American companies send these shows north because they're cheaper to produce here and get all sorts of tax breaks from the Canadian government. I get called in to pitch and write episodes fairly regularly. The pay is good, but there are plenty of limits as to what I can get away with. The sensibilities of the broadcasters don't often swing towards my pitch black sense of humour. It's disconcerting to watch my deadpan jokes being turned into slapstick. Still, I get to amuse myself by trying to slip things past the Standards and Practices people. You know, the usual stuff -- homosexual and drug abuse subtext, porn references, oral sex jokes. I can only hope I'm warping many young minds, if only subconsciously.

As for film, I've been paid to write a couple of features, but who knows when or if they'll ever get made. I have a short film called Ashes to Ashes that was shot in San Francisco last year.

It's a necrophiliac murder mystery that's in post production now, so hopefully we'll see it soon. You can check www.ashestoashes.net to see what progress has been made.

DS: How has your having written for comics helped with this?

SS: It was my comics work that first made an impression with local industry folk. We're talking only a couple of people here, but it slowly got the ball rolling when my interest in screenwriting was revealed. I already had a few scripts lying around, one of which had been briefly represented by an agent in Chicago, so I wasn't quite a neophyte. But really, any potential career I had going was suffering thanks to my complete lack of contacts. Comics helped get those first few people on my side. Even now, they continue to win some producers over. My agent has a pile of Longshot Comics she sends out occasionally to introduce me as a writer. A couple of times they've hit big, and led to long term professional relationships.

DS: Are you still working in the comics field?

SS: I try to as much as possible, and I'm always willing to hire myself out for individual scripting jobs. A story I wrote for Narcoleptic Man years ago recently hit the shelves. Another one- shot special I worked on last year should be out one day soon I hope.

Then there's the big projects I'd like to get off the ground. Unfortunately, most of them require me to hook up with an artist who can handle the drawing aspects that are beyond my abilities. Finding someone reliable has been an ongoing problem of mine for years.

A third Longshot edition remains on my plate. I have a lot of material there, but plenty more to write before I can even think about setting a publishing date. This one takes place earlier in history than the other two, so the research challenges have increased sharply.

DS: Do comics make the world a better place?

SS: Absolutely. I often find what's going on in comics to be more interesting and challenging than what's happening in any other medium. Because comics remain such a fringe form of expression, we can get away with much more. I myself have broken court-ordered publication bans and international forgery laws as a matter of routine. No one arrested me. No one cared. Because no one in the establishment was watching. True, there's relatively few people who care about comics, but that's what gives us freedom.

For an art form that is both visual and literary, it's a widely available and inexpensive means of expression. You really can start your very own publishing empire with pen and paper and just a couple of bucks in your pocket. Printing your comic professionally and distributing it internationally is within most people's means -- and you don't need to answer to publishers and editors if you don't want to. Many regular folks do it all by themselves. Can't afford a couple thousand bucks worth of printer bills? No problem. Take it to your local photocopy joint and make it a minicomic. Once you're done, send copies out in the mail to other self publishers you've heard about. Before long, you'll be plugged into the small press network. You might even earn yourself some fame around the world. Really.

Try doing that with film or television or books or even music. You'll probably end up poor and ignored.

DS: Were you ever worried that letting people know of your interest in comics might have meant that people would take your writing less seriously?

SS: It's always a risk, since so many people still equate comics with dumb superhero rags. But provided I can hook them up with copies of my work, I don't worry about it. They only have to look at a panel or two to figure out I'm doing something different.

Recently, I had a nice experience in which my comics actually gave me more credibility as a writer. I was at a taping of a sitcom episode I wrote and the cast was buzzing because some of them had just realized that I was the same Shane Simmons who did The Long and Unlearned Life of Roland Gethers (still well known in Montreal where there are all those cheap minicomic editions floating around). Suddenly I was no longer just another hack screenwriter -- I was that guy who did the cool comic.

Sometimes it's hard to say which writing gig is looked down on more: comic scripting or screenwriting.

DS: What should the Small Press creator bear in mind when looking for a new home?

SS: Space. Lots and lots of space for all those comics you've probably accumulated. Also, in my case at least, I like any building that isn't currently on fire. That's always a big plus.

Contact Shane at shaneSTOP-@-SPAMashestoashes.net

Related Links

City Pages review Longshot.

Shane's bio and a film outline.

Shane reviews Fly By.

French review of Shane's Longshot comics.

Review of Arrowdreams, a anthology Shane contributed to.

Reviews of Shane's work at Broken Pencil

Mention of Shane's contribution to a Magnetic Ink comic.

Internet Movie database for Shane

Shane is up for a Writers Guild of Canada award.

If you have a comment or question about Small Press then feel free to contact me