Michael L. Fleisher: Never in the Wrong Place at the Wrong Time

Michael Lawrence Fleisher (1/11/1942 - 2/2/2018)

me: A good number of the story-lines you wrote back in the 70s and 80s have been collected in trade paperbacks. Have you been surprised by current interest in that work? What do you think keeps readers interested in them?

Michael L. Fleisher: Please try to understand that I have, at present, very little involvement with the comic-book fraternity, which is another way of saying that I don't know. I think I wrote some wonderful stuff, some not-so-wonderful stuff, and undoubtedly some wretched stuff. The wonderful stuff, whoever writes it, will always be around.

I'm confident his work both in comics and anthropology will live on. My condolences to his family and friends.

This interview was originally published by Comicsbulletin.com in February 2008

Michael

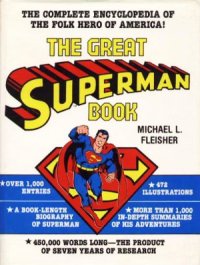

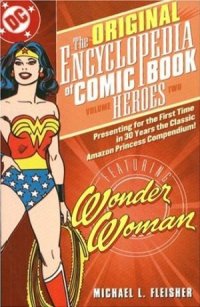

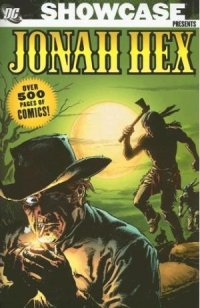

L. Fleisher's comic-book writing career spanned two decades in which

he authored approximately 700 stories for DC, Marvel, and other

comics publishers. His work on series such as The

Spectre and Jonah Hex is still highly

regarded, as is his work on the Encyclopedia of Comic Book

Heroes. After a widely reported libel case his comic output

declined, with his last published comic assignment appearing in the

UK anthology 2000AD in 1995. With his work on

Jonah Hex and the three titles in the

Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes series being

reprinted in recent years, plus a newly published novel set in the

comics industry, it seemed like a good time to have a chat.

Michael

L. Fleisher's comic-book writing career spanned two decades in which

he authored approximately 700 stories for DC, Marvel, and other

comics publishers. His work on series such as The

Spectre and Jonah Hex is still highly

regarded, as is his work on the Encyclopedia of Comic Book

Heroes. After a widely reported libel case his comic output

declined, with his last published comic assignment appearing in the

UK anthology 2000AD in 1995. With his work on

Jonah Hex and the three titles in the

Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes series being

reprinted in recent years, plus a newly published novel set in the

comics industry, it seemed like a good time to have a chat.

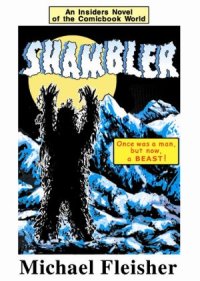

Darren Schroeder: The synopsis for you your new novel Shambler marks it as firmly set in the comics business. After so many years where you seem to have gotten along quite fine without the world of comic books what prompted you to revisit it?

Michael L. Fleisher: I actually wrote Shambler in the mid-1980s but I was in college from 1987 to 1991, and so my time was split between writing comics and going to school. And right after I graduated, I moved from New York to Ann Arbor, Michigan, to attend graduate school. I wrote my last comic-book story, for 2000 AD, in the summer, right before my classes started.

Earning my doctorate in anthropology took seven years, including two full years in Tanzania, where I did my fieldwork, and one year in New York writing my dissertation. So Shambler kind of got left behind.

Starting in 2002, I began earning my working as a freelance anthropological consultant carrying out research assignments for humanitarian organizations in the developing world, a job I still do. I've worked in eight African countries and two Asian countries.

Fairly recently, I got out all my old manuscripts from storage and made a project of entering them into my computer as a way of conserving them. (None of my books was written on a computer, because I didn't learn to use, and acquire, a computer until I entered grad school.

My pile of manuscripts included Shambler. I thought it was terrific, so I made a project of turning it into a book.

DS:

Was there anything in the book that you look at now and think

that's so 80s?

DS:

Was there anything in the book that you look at now and think

that's so 80s?

MLF: I'm anything but a comics historian. But that certainly seemed to be the era when the superheroes stopped being so squeaky clean, when the personalities of the heroes---especially their darker side (think Dark Knight)---began to be explored and to be fair game for stories.

That was also, if I'm not mistaken, when, if you were hip enough, you began to see porno queens being utilized as artists' models for female comic-book characters.

The pornography/comic-book nexus is a major theme of my book.

DS: You've mentioned the appearance of porn stars as reference material for artists, in what other ways do you see them intersecting?

MLF: I confess I may have exaggerated. That is the only way I can think of. Kevin Ellman, Shambler's comic-book-writer protagonist, is obsessed with pornography.

DS: What sort of writer is Kevin Ellman; a big name success, journeyman or a rising star?

MLF: Best known for his work on a comic-book series called The Shambler, Kevin is now in the midst of a serious dry spell.

DS: From the books promotional material prospective readers learn "Kevin Ellman became a casualty of this new fantasy landscape and tumbled into a nightmare world." In what way does Kevin become a casualty - is this in a psychological or more fantastical sense?

MLF: I think I can be forgiven for not wanting to reveal too much. Kevin's fantasies definitely play a role, but we are talking here about the real world, not some otherworldly fantasy world.

DS:

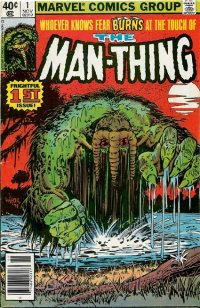

"The Shambler, a strange beast-man, half-insane but intensely

empathic" - Sounds similar to a certain Man-Thing. Was that a

character you particularly enjoyed writing?

DS:

"The Shambler, a strange beast-man, half-insane but intensely

empathic" - Sounds similar to a certain Man-Thing. Was that a

character you particularly enjoyed writing?

MLF: Admittedly, my memory is no longer as good as it was, but I have no recollection of ever having written a Man-Thing story. In any event, the Shambler---who is clearly described in the novel as a Himalayan snow monster, "swathed in animal pelts, and "formed entirely of snow and ice"---cannot possibly confused with the Man-Thing.

**Michael wrote the first three issues of Man-Thing Vol. 2 (1979/80)**

DS: How autobiographical is Shambler?

MLF: Not at all.

DS: Is it a book for comics fans or a more general readership?

MLF: Weird as it may sound, I never give any thought to the subject of audience and I am tone deaf when it comes to knowing what is and what is not commercial. Particularly with my novels, I've been spectacularly unsuccessful commercially, but I tell myself that nobody's paying me to do this sort of writing---I suppose you could call it a hobby---so why should I bother myself with whether or not people would like it?

I do think that Shambler provides a very interesting perspective on the comic-book scene in the period I write about. But of the themes I deal with, I think the most interesting is the nexus of comic books and pornography.

DS: The blurb for the novel mentions "publishers populated the comic-book universe with them [flawed anti-heroes] and sent them forth into battle with masters of super-villainy even darker than the flawed anti-heroes who fought them." What long term effects do you think that move has had on US comics?

MLF: I adore the flawed anti-heroes. I think the goody-two-shoes heroes are boring!

DS: They certainly are, but some readers feel that things these days have gone too far. Did you see signs of that when you were following comics?

MLF: Not in my time. Remember, I have not read a comic book since 1991. And I have no idea whatsoever what the long-term effects on US comics will be? I haven't read or written a comic book story in 17 years, but I've got to assume that whatever phase we're in will eventually be supplanted by a different aesthetic. This is the way of the world.

DS: A book looking at the comics industry by a comics writer might be seen by some as a possible polemic, or someone out to settle old scores. Will readers find either?

MLF: Absolutely not! Shambler is not a polemic. It is a story, a fiction. And I have no scores whatsoever to settle. I loved my time in comics.

DS: I'd assume that Shambler is set in New York where the comics industry was based in the 70s and 80s, and for the most part still is. Does the city have a role to play in the novel apart from it's physicality?

MLF: Indeed it does. A good part of the story is set in the old, rundown, seedy Times Square in a porno emporium of that era which I have pseudonymously renamed the Pornomart. Kevin Ellman, the novel's protagonist, lives in a brownstone on the Upper West Side, nearby Central Park, in the era prior to that neighborhood's becoming gentrified.

DS: Does the book deal with any of the practical realities of the comics business that might give readers a sense of how it was back then?

MLF: It does provide a excellent window into the comic-book milieu at that time.

DS: Did you and artist Russell Carley give any thought to doing more Shambler artwork aside from just the cover?

MLF: No.

DS: Looking back, what was the most positive aspect of writing comics back in the 70s for you?

MLF: I had adored comics as a youngster, as an adult I very much enjoyed writing them, and I had the good fortune to work with some very talented people.

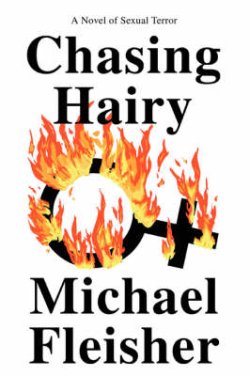

DS: I see that

you have also released a new edition of Chasing

Hairy.

DS: I see that

you have also released a new edition of Chasing

Hairy.

MLF: This is true. It had been out of print for some time, and I thought it would be nice to have it available again.

DS: What was it about iUniverse that made you publish through them?

MLF: The commercial publishing houses are interested primarily in marketing best-sellers, but the work I do is not at all likely ever to command a mass audience. Print-on-demand publishing makes it possible for anyone who wishes to-within the space of about a month-to see his or her manuscript turned into book and made available to the public on such websites as Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Books-A-Million. For me it has been an ideal way to go.

DS: How much editing did you do to the book as you transferred into the computer?

MLF: None

DS: What storytellers from your youth got you interested in becoming one yourself?

MLF: I wanted to become a novelist from the time I was very young, certainly by the time I was in high school and afterward. I loved Kerouac, Faulkner, Beckett, Genet, Burroughs---experimental writers. But I'm not an experimental stylist or innovator. I'm pretty much straight down the middle.

DS: Does the comics industry hold any appeal to you now as a way to make a living?

MLF: No, I don't think so. I'm in a different phase of life now. I'm doing other things.

DS: Some of the people involved in your well-documented libel case still seem quite touchy about the subject, is it still a live issue for you?

MLF: No.

DS: Their has been some speculation that the result of the libel action left you broke, bitter and angry. Was that ever the case?

MLF: No. My lawyers took the case on a contingency basis and the entire episode never cost me a dime. I was content to have had my day in court. I was neither bitter nor angry.

DS: Regarding your work with 2000AD anthology - What sort of differences did you notice between the UK editorial approach and that of US companies?

MLF: Only that they had a sensibility and a sense of humor that was quite different from ours.

DS: How did that affect your work for them?

MLF: I was not able to do my best work for them.

DS: What was it about it about the 2000AD work that you were unhappy with?

MLF: It has been 17 years since I wrote my last one, and frankly I cannot recall much about the stories I wrote. I admired the work the Brits did, but I never really succeeded in capturing the sensibility, and I know that it was not my best work.

DS: What was it like to no longer be tied to comic storytelling as your professional and creative outlet - did you miss it when you stopped?

MLF: No. I went to grad school, became an anthropologist, went on to other things.

DS: Did you find that the discipline picked up from monthly deadlines helped with getting the writing done on the thesis?

MLF: No. I have a brother, an attorney, who is just like me in this respect: neither of us has ever missed a deadline.

DS: What motivated your move to academic study?

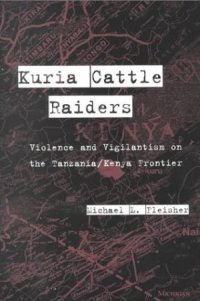

MLF: By the early 1980s, I was making enough money

that I could afford to take an exciting vacation nearly every year.

In 1982, I went on a wildlife tourism expedition to Tanzania's

Serengeti Plain. In 1983, I went to the Galapagos Islands off the

coast of Ecuador. In 1984, I went on a trek through New Guinea.

New Guinea is a wild and extraordinary place. It, more than any other

place I'd ever been, inspired me with the desire to learn more about

other cultures, about how the people in other societies live.

When

I returned to New York, I telephoned the admissions department at

Columbia University and asked if I could enroll in an anthropology course.

Not an anthropology program, I insisted---only a single course. I

ended up enrolling in Anthropology 101. It stole my heart away. I

took a full load of anthropology courses and all the other courses

needed for a B.A. degree. And I kept up my full load of comics

writing during that period. I did very well. I applied to the

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and earned a doctorate in

anthropology there. For the fieldwork for my dissertation, I lived in

a village in Tanzania for just under two years and studied the

phenomenon of commercialized cattle theft---i.e., the theft of cattle

in Tanzania for market sale in neighboring Kenya. My book

Kuria Cattle Raiders: Violence and Vigilantism on the

Tanzania/Kenya Frontier. (Univ. of Michigan Press) is based

on the research I did there. Since then, I have been earning a living

as a freelance consultant carrying out research projects for

international humanitarian organizations in the developing world. In

2007, my work took me to Afghanistan and Angola.

When

I returned to New York, I telephoned the admissions department at

Columbia University and asked if I could enroll in an anthropology course.

Not an anthropology program, I insisted---only a single course. I

ended up enrolling in Anthropology 101. It stole my heart away. I

took a full load of anthropology courses and all the other courses

needed for a B.A. degree. And I kept up my full load of comics

writing during that period. I did very well. I applied to the

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and earned a doctorate in

anthropology there. For the fieldwork for my dissertation, I lived in

a village in Tanzania for just under two years and studied the

phenomenon of commercialized cattle theft---i.e., the theft of cattle

in Tanzania for market sale in neighboring Kenya. My book

Kuria Cattle Raiders: Violence and Vigilantism on the

Tanzania/Kenya Frontier. (Univ. of Michigan Press) is based

on the research I did there. Since then, I have been earning a living

as a freelance consultant carrying out research projects for

international humanitarian organizations in the developing world. In

2007, my work took me to Afghanistan and Angola.

DS: Some of those are troubled places to visit, have you ever felt like you might have been in the wrong place at the wrong time?

MLF: No.

DS: What sort of projects has your consultation involved?

MLF: Locating and mapping landmines in Ethiopia; human trafficking in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and Burundi; informal village demining (i.e., landmine removal by ordinary villagers without the benefit of mine detectors, protective clothing, or medical backup) in Cambodia and Afghanistan; tracking pastoralist migratory patterns in Ethiopia; etc.

DS: Is the first world helping or harming the developing world?

MLF: I suppose helping in some ways, harming in others.

DS: Have you kept in touch with DC/Marvel comics over the years?

MLF:

I would have to say mainly DC, which, as you may already know, has

brought my 3-volume Encyclopedia of Comic Book

Heroes back into print.

MLF:

I would have to say mainly DC, which, as you may already know, has

brought my 3-volume Encyclopedia of Comic Book

Heroes back into print.

DS: Did you have much involvement with their re-release?

MLF: I wrote the introductions to the volumes.

DS: Was the choice of characters based on any personal preference on your part or an assessment of importance?

MLF: First of all, I need to say that Carmine Infantino, at DC, granted me extraordinary access to the DC Comics library as well as permission to utilize and publish illustrative materials. My original, wholly unrealistic, plan was to produce an encyclopedia of all the DC and Marvel titles. (I even had a plan to do one of The Spirit.) But, of course, it had been a long, long time since I'd read a comic, and I had no idea whatsoever of how many titles there actually were. Soon enough, of course, reality set in, and I dedicated my energies to the DC big three: Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman.

DS:

Which of the three characters you researched for the encyclopedias

did you think was the most interesting, and why?

DS:

Which of the three characters you researched for the encyclopedias

did you think was the most interesting, and why?

MLF: As a boy, my favorite comic-book character had been Batman. But in writing the encyclopedias, I was mainly focussed on documenting, in very great detail, the characters' oeuvre, in the way that great literary works of the past are documented.

I think that readers have been impressed by the extraordinary attention to detail in the encyclopedia; the inclusion of a synopsis of every single story in the time period covered; in the precise referencing to the comic-book sources from which every fact in the encyclopedia was obtained; and the effort to delve in the psyches of the characters.

DS: Was it fun looking through the DC Archives?

MLF: Not especially, no. I mean no disrespect when I say that I was not a fan. I had read comics avidly as a kid, in the 1940s and '50s, before fandom as he now know it ever existed. By the time I first entered the DC archives, I was a professional writer working to put a book together.

DS: What was the DC Comics archive like?

MLF: As described in the introduction to each of the volumes of The Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes, it was "a medium-sized, one-room library, lined with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves," containing two copies each of every comic book that DC Comics had ever published up to that time.

DS: Any plans to continue the series with other characters?

MLF: No plans as yet. But I do have in my possession the manuscript for a Golden Age Flash (Jay Garrick) volume; a Hawkman volume; a Green Lantern volume; and a few other, smaller manuscripts safely tucked away.

DS: Do you get many folks asking "Are you the Michael Fleisher who wrote [insert title] comic?" these days?

MLF: No.

DS: A good

number of the storylines you wrote back in the 70s and 80s have been

collected in trade paperbacks. Have you been surprised by current

interest in that work? What do you think keeps readers interested in

them?

DS: A good

number of the storylines you wrote back in the 70s and 80s have been

collected in trade paperbacks. Have you been surprised by current

interest in that work? What do you think keeps readers interested in

them?

MLF: Please try to understand that I have, at present, very little involvement with the comic-book fraternity, which is another way of saying that I don't know. I think I wrote some wonderful stuff, some not-so-wonderful stuff, and undoubtedly some wretched stuff. The wonderful stuff, whoever writes it, will always be around.

DS: Are there any characters from your comic career that you have any burning desire to revisit now?

MLF: If by "revisit," you mean "write" again, I'd have to say no.

DS: What do you think of as your best work in the comics industry, and what marked it as such for you?

MLF: My very best comic-book work, by far, was my lengthy run on Jonah Hex. My friend Louise Simonson, the wife of Walt Simonson, once referred to me as "the soul of Jonah Hex." All I can say is that I have never written anything else that has flowed so effortlessly for me or that has taken hold of me so completely.

DS: I

hope you don't mind, but I have to ask at least one Jonah Hex fan boy

continuity question: At the end of your run on Jonah Hex/Hex, Jonah

is left sitting looking at his stuffed corpse, happy at least that it

proves he would somehow find his way back to the old west. Did you

have any definitive plans for how he might have gotten back that you

can share to help satisfy the curiosity of the fans?

DS: I

hope you don't mind, but I have to ask at least one Jonah Hex fan boy

continuity question: At the end of your run on Jonah Hex/Hex, Jonah

is left sitting looking at his stuffed corpse, happy at least that it

proves he would somehow find his way back to the old west. Did you

have any definitive plans for how he might have gotten back that you

can share to help satisfy the curiosity of the fans?

MLF: I'm sorry to say, I can't. I have no background or very much interest in sf. I [admit] extradimensional worlds and time travel aren't my cup of tea either. I wish I had the talent for it, but I don't. But when DC cancelled the title, I did my level best to have Jonah segue into the future in an effort to keep the character alive. Mark Texeira produced some phenomenal artwork for Hex, but my best work is displayed in the Wild West version.

DS: It is widely assumed that the proposed Showcase Presents: Jonah Hex Vol. 2 was "postponed" because the residuals mandated by the contracts used when the original work was commissioned are more than DC is willing to pay. Has anyone from DC contacted you about the issue?

MLF: Nope, no one has.

DS: Do you have any more stories regarding the world of comics left to write?

MLF: I don't think so.

DS: Has your son ever expressed any opinion on your comic work?

MLF: Not yet. Thomas is not quite 5 years old and is pretty much hooked on Thomas the Tank Engine. But given a few more years, I know he'll be into comics. How could anyone not be?

DS: Do you have any advice for aspiring comics or prose writers?

MLF: 'Fraid not.

DS: What's next for Michael Fleisher?

MLF: Grow old gracefully. Enjoy my wife and little boy. Maybe write another book.

My thanks to Michael for talking the time to answer my questions. Extracts of Shambler are available to browse at iUniverse's website.