Raptus 2003: Norway's 8th year of an international comics festival

Posted: Tuesday, September 30, 2003

By: Jenni Scott

If you're a regular at the Bristol comics festival in May, you will probably have heard of the Norwegians Arild and Frode, who come to the event bringing their akavitt, hard salty meat, and lively company. You may also have heard that those same attendees run an international festival of their own, on a larger and even more general scale than the Bristol one; this year, I decided to see for myself what comics on the other side of the North Sea are all about.

The Raptus Festival, Bergen: Government Funded since 1995

Back in 1995 the Norwegian government decided that comics should be encouraged to develop as an important branch of Norwegian culture. Tove Bakke from the Department of Culture contacted a friend of hers to ask who in Bergen would be the right person to organize and front an International Comics Festival -- this from a country with no history of comics events other than an art exhibition in the seventies and a small gathering of professionals in 1993.

The nominated person, Arild Wærness, was sat in the sitting room of Tove's contact at the time of that phone call; talking about comics, no doubt. Arild had created a prozine and run a comic shop, as well as having the requisite collection of some 3000 comics, and took on the task of starting up the festival, running the first event in 1996 with the aid of some two or three co-organizers and not far off the same number of gophers. That first year was a quiet one in comparison to what I saw this weekend -- at that initial gathering, the attendance was small and the accommodation basic (it was held in a Student Hall of Residence). The organizers persisted, encouraged by Tove Bakke's promise to bring a big Nordic Comics art exhibition to the second year's event; and that second time saw a bus-load of Norwegian comics artists making the journey from Oslo to Bergen and much higher attendance figures overall (around the thousand mark at that point). This year, the event was held in the Bergen Conference Center with a main hall seating 500, three other smaller halls, with computers, light boxes, and projectors liberally supplied for the panel items, and a guest list featuring creators from the US, UK, Spain, Chile, Denmark, and other countries.

That first year was a quiet one in comparison to what I saw this weekend -- at that initial gathering, the attendance was small and the accommodation basic (it was held in a Student Hall of Residence). The organizers persisted, encouraged by Tove Bakke's promise to bring a big Nordic Comics art exhibition to the second year's event; and that second time saw a bus-load of Norwegian comics artists making the journey from Oslo to Bergen and much higher attendance figures overall (around the thousand mark at that point). This year, the event was held in the Bergen Conference Center with a main hall seating 500, three other smaller halls, with computers, light boxes, and projectors liberally supplied for the panel items, and a guest list featuring creators from the US, UK, Spain, Chile, Denmark, and other countries.

From that time to this, the Festival has gathered a number of co-organizers (most prominent in terms of the Bristol convention would be Frode Haaland, another regular UK visitor), changed venue more than once (this year was the first time it was held in the Conference Center), gathered around itself a list of volunteer helpers (distinguished by their yellow t-shirts) numbering in the hundreds, and invited international guests of the stature of Will Eisner (this year's keynote speaker), John Buscema, Sergio Aragones, Carlos Nine, and Mort Walker to name only a few.

This year saw a growth of the organizers' ambition and organizational powers that almost overstretched them, but as with most things done with good humour and good will, in the end all present found the proceedings to be a blast.

Discussions, Digressions, Demonstrations, and Difficulties

The program this year was visibly over-stuffed, to the extent that it was difficult on occasion to choose between three competing options. I certainly have no complaints with the fact of having a loaded panel program; other European festivals I've been to have been rather light on discussions, and of course even in UK- and US-style conventions the discussions are often weighted on the side of silliness; fair enough for an selection of the items, but not something to base a whole convention program around.

Bergen provided a range of different kinds of program items, which was great to see:

- Highlights of the visiting artists (Aleksandar Zograf talking about Dreams and the Subconscious in Comics Writing, Carlos Ezquerra on working with Garth Ennis, Lew Stringer on his series Suburban Satanists which is being translated into Norwegian).

- Discussions of topics of general interest (Classic UK Comics, discussed further below; the Stripburger crew on Comics from the Other Europe, presenting Eastern European comics)

- Lots of signings; in addition, Barrie Mitchell and John Cooper initiated the idea of selling original artwork at the event; despite a slow take-up this year, maybe this will be a growth area in future years

- Parties and rock n roll; I didn't see the rockabilly performance of Rex Rudi myself, but I'm told that the live music by the protagonist of a cartoon strip (illustration) was great fun. On the Saturday night, also, there was a festival meal: over 200 attendees and invited guests, seated willy-nilly and mixed up; a three-course meal provided for a reasonable price for ordinary attendees as well.

- Particularly exciting was the thread of practical program items: Dave Windett has run comics classes for a few years now, and this year exceeded himself in producing around 20 hours of classes over the week up to and including the festival; the UK invitees had sessions on drawing and writing their specialities (Romance and Girls comics for John Armstrong, Sports and Action comics for Barrie Mitchell, Structuring a Manuscript by John Freeman).

In addition, there was a decent café to retire to; an exhibition of artwork was set up at one side of the food area so you could wander around munching a sticky bun and peering at original artwork and comics-influenced images such as a Mona Lisa with Nemi's head.

Of course there was also the opportunity to buy comics: Norwegian (second-hand and new) and from further afield (the publishers of Stripburger, from Slovenia, were present, as well as Swedish, British, and American comics publishers and retailers).

Although there was so much on offer, it was not always as well-set-up as the above might lead you to believe. The conference center was large, and on several floors; though the signage was clear enough as to where events were located, they weren't always run on time (each item was due to run back to back, but in fact often twenty minutes could go by in between the events). The people on each panel weren't always clear about what they were to be doing (there was a call round the breakfast room at 9:45 on Saturday, for people to join in on Will Eisner's Shop Talk starting at 10 am), or even when (memorably, Carlos Ezquerra's talk about working with Garth Ennis had to be postponed by an hour as he couldn't be found at the originally-advertised time). It did happen in the end, though, which was great for the handful of us who turned up at the replacement time...

I felt that the lack of description for each panel item was a shame -- of course the brief blurbs that were given for each one were often in Norwegian ('Latinamerikanske serietradisjoner' to describe the talk by Themos Lobos of Chile) and I suppose longer ones would also be. But the British guests invited to talk about Classic UK comics, for instance, could have done with some more information having been given about their work prior to the start of their panels; and I think now that I would have enjoyed going to see something by Themos Lobos if I'd realised a bit more about what he would be talking about.

I felt that the lack of description for each panel item was a shame -- of course the brief blurbs that were given for each one were often in Norwegian ('Latinamerikanske serietradisjoner' to describe the talk by Themos Lobos of Chile) and I suppose longer ones would also be. But the British guests invited to talk about Classic UK comics, for instance, could have done with some more information having been given about their work prior to the start of their panels; and I think now that I would have enjoyed going to see something by Themos Lobos if I'd realised a bit more about what he would be talking about.Perhaps more damaging, though quite understandable and difficult to avoid, were the technical difficulties; each room was set up with great equipment -- microphones, PCs, projectors, and document cameras to display artwork on large screens as it was drawn. Unfortunately this was also capable of causing problems; Pat Mills struggled with his PC slideshow of Charley's War artwork, the set-up time added significantly to the delays between items, and of course the simple fact of having microphones doesn't mean that people will actually either speak into them or project their voices...

Having said that, in future festivals I'm sure the technology will come into its own, perhaps with a little more spacing between program items. Nothing can beat the convenience of illustrating a talk about a specific comic with large-scale, readable projections, or more excitingly having artists draw their characters, live, in front of the panel. It also means that at the end, there's some artwork to give to excited volunteers or to stash away in the Raptus archives...

Classic UK Comics Highlighted

I blush to admit it (well, no, not really) but despite what I said at the beginning, my prime motivation for coming over to the Bergen festival this year was not to see Norwegian comics but rather to see some British comics history treated with the sort of attention that they never have been back in the UK. British creators such as Mike Collins and Dave Windett have been attending the Bergen festival for a few years now (indeed, they are now getting work in the Scandinavian market), running comics workshops and classes and doing signings, but this year was something special for those interested in British-oriignated comics of twenty, thirty, forty years ago.

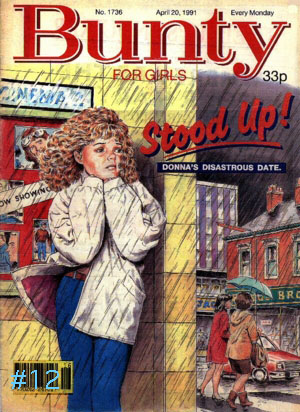

I have two particular areas of interest in the comics medium: one to do with small press and independent publishing (tying into the annual Oxford convention, CAPTION), and one to do with British seventies girls' comics, and among those, specifically one called Jinty (published by IPC / Fleetway from 1975 to 1982). I keep a sharp eye out for other related comics -- Tammy and Misty from the same publisher, and Bunty from rival publisher DC Thompson -- and am interested in the contrasting comics of an earlier age - Judy, Sally, the long-running Girl, and other titles that have mostly been ignored by comics aficionados (and aficionadas).

There was no way for me to resist the trip to a convention that promised two particular names: Pat Mills, the moving force behind the seventies IPC titles, and John Armstrong, the girls' comics artist par excellence (though rarely credited, his art is epitomized by the long-running Bella gymnastics story in Bunty). Also present were John Cooper (artist on Judge Dredd, Johnny Red, and various war stories), and Barrie Mitchell, football artist on Roy of the Rovers and Scorer (and even some girls stories, both at the beginning of his career and currently in DC Thompson's Mandy, which is sold only on the continent, to huge sales in Germany and Norway). Veterans of the studio system and the isolationist way that artists and writers usually worked at that time, many of them hadn't even met (despite having worked together for many years) until they were brought together for this weekend's panel on Classic UK Comics and their history.

You may wonder why there should be a panel on this topic in a Norwegian festival, of all places. The answer lies in the great amount of republishing and redistributing of British comics throughout Europe, mostly invisible to us still on the island except for on the odd visit to Belgian or Spanish fleamarkets or the like, which may turn up an unexpected Jinty reprint in album format or a tattered football mag featuring a rettled 'The Goalkeeper Had Guts'. (Barrie Mitchell was brought one of these for signing during the festival, much impressing him -- and surprising him, because obviously not a penny of the royalties had ever made its way to him.)

John Freeman, the panel moderator, has a background in Marvel UK and other British comics publishers during the nineties. He summarised the recent history of the British comics market: through the 1950s - 1970s, weekly comics for children were an important publishing phenomenon, selling in the area of 200,000 - 300,000 per week each title. There were numerous competing titles at a time, each tightly defined; in the case of Tammy, Misty, and Jinty, for instance, the former had realistic stories, Misty was intended as 'Stephen King for girls', and the latter leaned towards the science fictional, though in the case of other titles the market could be defined more crudely; one, Romeo, was aimed at girls who wanted their white knight to sweep them off their feet but whose hero was destined to never arrive. Secondary modern schoolgirls and pony-riding poshies would each have a title quite narrowly focused on their interests and reading habits.

Circulation figures, for both girls' comics and boys', started to dip in the 1970s; the reason was thought to be that the comics were too conventional. In the case of the girls' comics, the usual themes were pony stories, ballerina stories, school stories (possibly with mysterious foreign princesses, and wearing their Angela Brazil influences very much on their sleeve). You could also bet that there would be that the heroes and villains would be easily told apart from the word go.

Pat Mills was brought in with specific instructions to address the problem of girls comics and to make them less conventional. At 21, with a few other newcomers (mostly young men), he dived into this brief with gusto, writing stories with an edge that had never been seen before, and creating a number of titles (Jinty and Misty in particular, though he stayed closer to the latter)which pushed a publishing policy of what can be seen in retrospect as the brightest wave of girls stories ever seen in the UK -- though in the end, it was sadly short-lived.

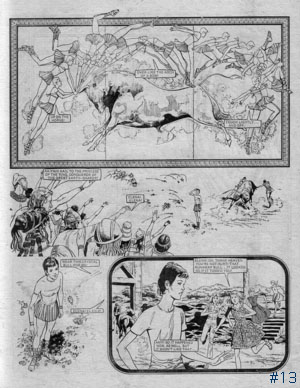

The new wave of girls stories and story-papers (rarely called comics) verged on the ridiculous but did it seriously and, in fact, amazingly successfully. Stories that featured never-before-seen cruelty and outright viciousness on the part of the baddies, odd though it may seem, led to great popularity in the readers' polls: we saw 'Slaves of War Orphan Farm' (exploitation of war orphans in the Second World War), 'No Tears for Molly' (a maid in Victorian times, bullied by the butler), 'Flipper Feet' (girl with big feet is bullied by her peers). Often, the stories went well beyond the bounds of credibility but still held things together: 'Becky Never Saw The Ball' because she was a blind tennis player (with a bandaged head, no less), and in another story, a blind horse was taught to showjump; but truth can be stranger than fiction, and in conversation afterwards, Barrie Mitchell recounted a true-life story about a blind showjumping horse... (For full examples, I must point you in the direction of a fantastic site, www.mistycomic.co.uk, that is republishing all the issues of Misty, 25 years to the day since they were originally published)

The revitalization of girls' comics worked well enough that Pat Mills was pulled off them (leaving the baton of the new wave in the hands of his colleague Malcom Shaw, writer on more oddball girls' stories than has ever been appreciated). His new brief was to create a boys comics on the same, groundbreaking, basis. That, of course, turned out to be first Action and then 2000AD. Some interesting new lessons were learned in the move from girls' stories to boys': emotions are not as popular as power, boys don't want to be chased but to be the chasers (an unpopular story called 'The Fugitive', in the early days of 2000AD, bore witness to that). The formulae developed for the new wave of British comics had to be changed for the new audience; adapted, and radically changed in some cases, such as in Pat Mills' ground-breaking anti-war story 'Charley's War', published in the war comic Battle that Mills launched.

The revitalization of girls' comics worked well enough that Pat Mills was pulled off them (leaving the baton of the new wave in the hands of his colleague Malcom Shaw, writer on more oddball girls' stories than has ever been appreciated). His new brief was to create a boys comics on the same, groundbreaking, basis. That, of course, turned out to be first Action and then 2000AD. Some interesting new lessons were learned in the move from girls' stories to boys': emotions are not as popular as power, boys don't want to be chased but to be the chasers (an unpopular story called 'The Fugitive', in the early days of 2000AD, bore witness to that). The formulae developed for the new wave of British comics had to be changed for the new audience; adapted, and radically changed in some cases, such as in Pat Mills' ground-breaking anti-war story 'Charley's War', published in the war comic Battle that Mills launched.In the meantime, though the new boys' comics were forging ahead, the girls comics fell back into the doldrums by the end of the seventies and beginning of the 1980s. The old school, conventional stories won back the field as some of the best writers moved to other pastures; girls were offered non-comics papers with aspirational articles on boys, makeup, pop music; and reading a weekly comic came to be seen as old-fashioned. Nowadays there is only one girls' comic published at all in the UK, with the long-running Bunty (featuring the hardy perennial 'The Four Marys') having folded in 2001. Even in the boys' market, though it still features 2000AD and its offshoot the Megazine, sales figures are an order of magnitude lower than the publishing heyday of the 1970s and earlier.

Despite the age and obscurity of these comics, I can recommend them whole-heartedly to anyone. The artwork is often stunning, with innovative but readable page layouts.

The stories have that edge of the absurd that makes them still lively today, an at their best are as enthralling as when read at the age of ten. No wonder people are starting to resurrect them with fansites and Ebay purchases.

Some links

The Raptus official site: http://www.raptus.no/

Misty comics fan site: http://www.mistycomic.co.uk

Charley's War fan site: http://charleyswar.tripod.com/

2000AD official site: http://www.2000adonline.com

John Cooper: http://www.jcoopart.com/

John Freeman: http://www.downthetubes.net (Contact John if you are interested in buying Barrie Mitchell's art)

Pictures - all by Jenni Scott ( http://www.comixminx.net ) except where noted:

1 - Leading man Arild Wærness.

2 - The main hall in full swing.

3 - Not all the visitors were from Norway.

4 - Katerina from Stripburger.

5 - The male/female presence was pleasingly balanced.

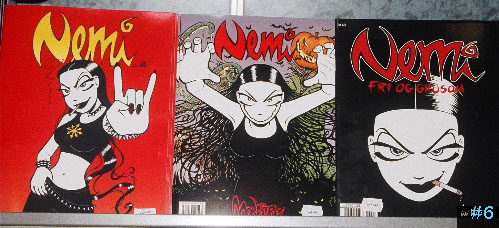

6 - And of course one of the biggest comics presences in Norway, Nemi, is created by a woman -- Lise.

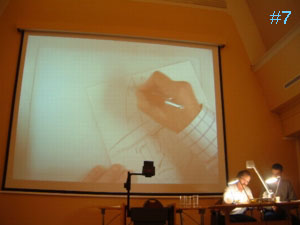

7 - The document camera got a workout with Carlos.

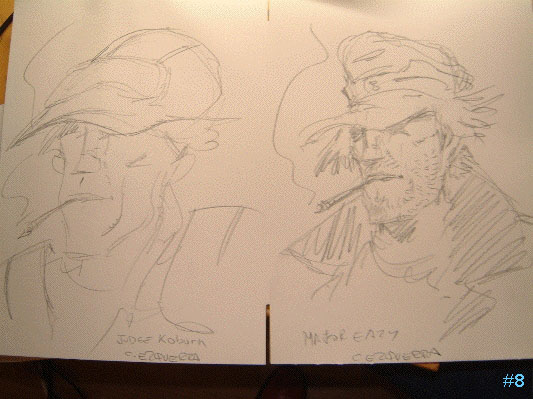

8 - Character recycling; nothing is wasted.

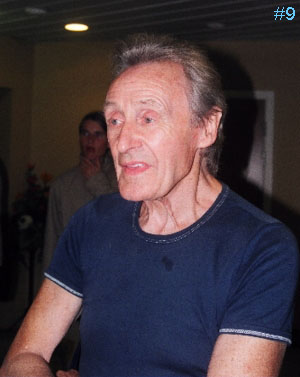

9 - John Armstrong, artist on Bella and many other girls' comics.

10 - Pat Mills, the moving force behind many girls' comics of the seventies.

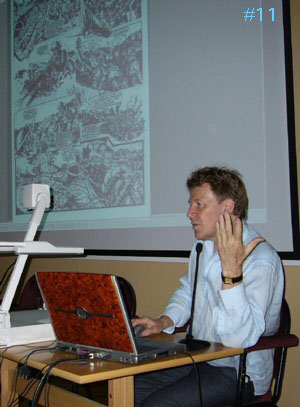

11 - Charley's War was discussed in detail in a separate session by Pat Mills. (from the Raptus official site).

12 - A late Bunty cover by the classic John Armstrong. (DC Thompson 1991)

13 - A beautiful page from Misty issue 30: Elena's Leap Through Time. (reproduced from Misty 1979)

If you have a comment or question about Small Press then feel free to contact me