Jason Lutes in Conversation with SBC

Posted: Tuesday, February 6, 2001

By: Darren Schroeder

The work of Jason Lutes has a revered status in the comics world which it well deserves. I've been following his work since people started saying nice things about Jar of Fools back in 1994, and Berlin is one of the very few comics that has stayed in my monthly order since a self-inflicted drop in income. My pleasure at Jason's agreement to be pestered interviewed was only tempered by the fear that he might turn out to have a head the size of the Goodyear blimp. I'm glad to say that while he has lots of interesting opinions about the comics medium and his own work, he manages to fit them in a standard issue head. Read on and fill yours.

Darren Schroeder: What is your full name?

Jason Haynes Lutes.

DS: Is your name pronounced "Lutes" as in "flutes" or "Lutes" as in "Klutz?"

JHL: Rhymes with "flutes."

DS: Age?

JHL: I'm 33 years old.

DS: Favourite web site?

JHL: Hmm. Y'know, I have to say that I don't really have one.

DS: Were comics a big part of your childhood or did you discover them at a later stage?

JHL: Before I could even read I would sit in my mom's lap and make her read comics out loud to me, so I'd say they were a big part of my childhood.

DS: Any favorites back then?

JHL: I loved all the old Kirby or pseudo-Kirby western comics, and some of my earliest drawing were copies of pages of Avengers comics. I remember also loving Captain America at a very early age.

DS: Was art an important part of your education?

JHL: Yes. Among the several elementary schools I attended were a few that were very free-form, allowing the kids to choose what subjects they wanted to focus on. For whatever reason -- I guess because it was a lot of fun -- I spent a lot of time doing art, and continued to do so as much as I could growing up. In high school in California it was more difficult, because public arts education funding had been practically eliminated, but I was lucky enough to have some great, passionate teachers and was able to keep doing it in a classroom setting, as well as my spare time.

DS: What was the first comic you published yourself and how did that come about?

JHL: I think the first comic I actually photocopied was a thing called Jeremy Noble, about an Indiana Jones-esque globe-trotting adventurer, which I drew when I was fifteen or sixteen. The first printed comic I published was Penny Dreadful Comics, a student comic book anthology I edited while studying illustration at the Rhode Island School of Design. It ran for six or seven issues, but I only had two stories among all of them -- Most of my energy was expended in organizing and producing it.

DS: How did you distribute your comics them?

JHL: Those comics were sold at school, during student sales or from a card table set up at the mailroom. In my last year at RISD, I started putting out minicomics by me and some friends, under the imprint Penny Dreadful Press. I sold those through local stores and through the minicomic mail network. We put out nineteen different Penny Dreadful minicomics in all, about six of which were by me.

DS: What sort of work were these?

JHL: They ran a wide range, from Mink, (by Joe Fullerton) the epic tale of a hungry mink chasing a vole through the woods, to Houdini, an anthology of comics about Houdini, to Boys and Girls, (by Jake Austen) a collection of funny strips about relationships. There were nineteen different minicomics in all, and each one was unique in terms of size, design, and content.

DS: Have you ever gone out with someone just because they had access to a photocopier?

JHL: Ha ha, no. If my reason for going out with someone was ever crass or pragmatic, it had to do with how hot they were or how good they were in bed.

DS: What materials and equipment do you use when drawing your comics?

JHL: I do my pencils with a mechanical pencil on vellum, and then use a lightbox to ink my pencils onto thin, plate finish bristol. My inking tool of choice is an Extra Fine Rotring Sketch Artpen, with a special refillable ink cartridge so I can use non-clogging, waterproof ink.

DS: Who do you see as the target audience for your work?

JHL: People who don't read comic books.

DS: How do you go about creating a comic that appeals to a non-comic audience?

JHL: I try to tell the story as clearly as possible, using only the most widely understood comics conventions and trying to build a vocabulary within the work itself.

Judging by most mainstream comics I see, it's no surprise that publishers have had a hard time expanding their audience. The majority of cartoonists demonstrate little mastery of the medium. They can often draw quite well, and can be partnered with a competent writer, but it's astounding to me how little such teams seem to understand and utilize the particulars of the medium of comics in order to tell a clear, accessible story. DS: What would be an example of such a particular in your work?

DS: What would be an example of such a particular in your work?

JHL: Well, on the most basic level, clarity is of paramount importance. There may be certain instances where you want the reader to work more and piece something together, but in general he or she should be able to absorb the story easily and with little effort.

So, I do things like never having more than a sentence or two in a word balloon, so it can be easily absorbed by the reader. In general, mainstream comics pack way too many words on the page, which hinders the comics reading process. The writers, for the most part, don't understand how comics work and don't trust the pictures to tell their part of the story. The end result is poor flow and less engagement on the part of the reader.

Or, for instance, take the most simple visual storytelling techniques. If a conversation is occurring between two characters, often the best approach is the most straightforward; I stage most conversations from eye level, and pay careful attention to the body language and facial expressions of those involved. Mainstream artists tend to overuse dramatic or skewed "camera" angles, unconscious of the fact that how you frame a shot is an inflection in itself, and can undermine what's being conveyed through the character interaction..

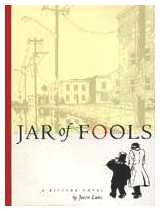

DS: The work that brought you to the attention of most comic readers was Jar of Fools. Were you surprised by the positive reaction it received?

JHL: I thought I was doing good work by my own standards, but I was certainly surprised that the book sold as well as it did. In some part that was due to Scott McCloud's independent promotion of the book, for which I'll always be grateful. He told a lot of people about it, and would send people to my table at conventions or show slides of my work during talks on his book tour. The book was an experiment for me, sort of like a high school project in my ongoing comics education. I think it was well-received partly because I set out specifically to tell a story that could be picked up and read by people who did not usually read comics, and partly because the reader could in some way participate in the same process of discovery I went through in its creation.

The book was an experiment for me, sort of like a high school project in my ongoing comics education. I think it was well-received partly because I set out specifically to tell a story that could be picked up and read by people who did not usually read comics, and partly because the reader could in some way participate in the same process of discovery I went through in its creation.

The relative success of Jar of Fools was in some way indicative of the state of the comics industry; within the field it can be considered a sophisticated work, but in any other medium the same story would probably seem hackneyed and cheesy. The standards in comics are quite low, as evidenced by all of the bad writers who continue to make money writing them.

DS: Is there any medium that can claim to be devoid of a mass of bad writers?

JHL: Certainly not, but I would argue that the ratio of bad to good writers in comics is much, much higher than any other medium.

DS: Why do you think that is?

JHL: Because it generally attracts writers who have failed or are not "good enough" to break into more lucrative creative fields. Even though 80-90% of any media tends to be crap, in comics the proportion is higher because it's considered a lesser, backwater medium, and so attracts lesser talents. Until a significant volume of better and more visible comics work is created, this will continue to be the case.

Proponents often despair over the ongoing lack of recognition despite a growing body of good comics work, but the simple fact remains that there still isn't enough of it to really make a strong, lasting impact on the book-reading public at large. The 1-2-3 whammy of Clowes/Ware/Katchor in the U.S. in 2000 has had the greatest positive effect since Maus, but the ripples will soon fade unless those books are followed up quickly by quality, high-visibility comics that come out on a more regular basis. And the odds are against that happening because it's such a time-consuming medium. But I'm fine with comics making the occasional cultural disturbance, and I feel like things will continue to improve for those of us who are producing non-mainstream work.

DS: How much re working did Jar of Fools require for the transfer from weekly strip to comic book?

JHL: Almost none. I think I redrew two pages. The story was intended to be collected in book form from the beginning. It ran one page at a time in The Stranger, a weekly paper here in Seattle, and if you didn't follow it on a weekly basis, the individual pages were like comics non-sequiturs. I did try to have each page contain an idea or feeling that would allow it to stand better on its own.

DS: How did your interest in magicians start?

JHL: In art school, two friends and I started to read up on Houdini. I don't remember which one of us became interested first, but we all proceeded to read everything about him that we could get our hands on. He led a fascinating life, and the three of us became thoroughly immersed in it for a short while. The result at the time was a minicomic called Houdini, which collected a series of short strips and stories about his exploits. From then on the magician -- or more acutely, the escape artist -- was a more resonant archetypal figure to me.

DS: Do you know any magic tricks?

JHL: When I got to the point in Jar of Fools where I realized Ernie was a magician, I began reading up more on magic, and studied card tricks. I practiced enough to pull off two or three tricks pretty well, but never developed anything close to what I would consider true "sleight of hand." It was more in the interest of research and understanding what went into learning a trick. I am currently long out of practice.

DS: Explain your use of the word "realized" in relation to your creative process.

JHL: Well, Jar of Fools was pretty much made up as I went along, in a very exploratory fashion. I made a lot of intuitive choices earlier in the story that would have to be fleshed out further down the line, but which at the point of inception were mysterious and seemingly random. This was important to Jar of Fools, as the narrative and its elements were drawn as directly from my unconscious as I could manage.

I use the term "realize" here to describe the point at which my conscious mind becomes aware of what my unconscious is trying to say, and formalizes it through a specific choice. For whatever reason, when Jar of Fools begins, Ernie is wearing a tuxedo. Shortly thereafter, he performs a magic trick, and only at that point does he become defined as a magician. What it may mean in any larger or personal sense is still open to interpretation.

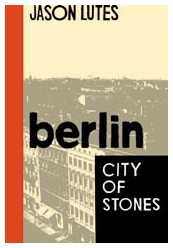

DS: If I suggested that Berlin seems much more structured would I be right?

JHL: Yes

DS: Do you prefer structured or free flowing writing.

JHL: Berlin is more structured because I wanted to have more of a blueprint before telling such a complex story. But the structure is loose enough for me to still have lots of room for improvisation, which is what keeps the storytelling process alive for me (and hopefully the reader). It's still a very exploratory process of discovery, just with more distinct goals.

DS: Writing doesn't seem the right word for comic creative activity, care to suggest an alternative?

JHL: It seems like no words used to describe the process of making comics in English really "fit" the broader definition of the medium. I can't think of an alternative to "writing," and most post facto terms (i.e., "graphic novel") ring false to me.

I'm all for using pre-established words like "comics" and "cartoonist" with enough frequency that people will eventually accept their broader meaning. For instance, "teamster" originally meant someone who worked a team of horses to pull a wagon, and now it means someone who drives a truck. Likewise, "cartoonist" once meant someone who drew funnybooks, and now means someone who simply draws comics. It's certainly an uphill battle, but I've never been happy with the other terms people have invented. I tell people I'm a cartoonist and I say that I "write" comics -- because cartooning is picture-writing, and all letterforms are anyway are highly abstracted pictures. I like "writing," actually, better than most of the other terms associated with the medium.

DS: David Copperfield and Harry Houdini, compare and contrast.

JHL: One of them sucks. The other one doesn't.

DS: What work have you been doing recently? JHL: I'm currently revising the first eight issues of Berlin so they can be collected in Berlin: City of Stones, which will be the first book of a trilogy about the city. I'm also adding pages to a story call The Fall, written by Ed Brubaker, which will be published by Drawn and Quaterly in early 2001. In addition, I'm drawing a short educational comic about dental health, to be distributed to Spanish-speaking migrant workers in Washington state.

JHL: I'm currently revising the first eight issues of Berlin so they can be collected in Berlin: City of Stones, which will be the first book of a trilogy about the city. I'm also adding pages to a story call The Fall, written by Ed Brubaker, which will be published by Drawn and Quaterly in early 2001. In addition, I'm drawing a short educational comic about dental health, to be distributed to Spanish-speaking migrant workers in Washington state.

DS: How do feel about Berlin: City of Stones being listed as one of the top 10 comics from 2000 in Time magazine before the book was even published?

JHL: I thought that was surprising and unfortunate. It can't be one of the best comics of 2000 is it's coming out in 2001. Somewhere in the publicity/solicitation loop a misunderstanding occurred.

DS: As you were considering revisions for the Berlin: City of Stones what were you thoughts about the first issue?

JHL: I'm unhappy with parts of the first issue, but then almost every cartoonist is unhappy with parts of anything a day after it's done. I like the overall structure of the first issue quite a bit, but some of the drawing is absolutely terrible, and I've tried to correct those instances. Some of the writing is pretty bad too, but I haven't had the leisure to rewrite the thing. I'll just have to live with whatever feels awkward or cheesy about the earlier issues.

DS: Conventional wisdom suggests that buyers want their comics on a regular schedule and that long periods between issues cause them to lose interest. How have the readers treated Berlin?

JHL: Oh, for the most part I think anyone who reads the book is pretty bummed out by the publishing schedule, or lack thereof. I certainly don't blame them. I wish I could produce the comic on a faster, more regular basis... I mean, I hate the fact that it's probably going to take me eight to ten years of my life to finish the story, when there's so much else I want to do.

On the upside, the goal is the collected books, and the readership we'll be reaching through bookstores -- although they'll still have to wait a long time between volumes -- will not be subject to having to read the thing in widely spaced twenty-four page chunks.

Some readers have lost interest in trying to keep up with Berlin and are just waiting for the book collections. The individual issues of the comic still sell reasonably well for its market, though, so some people out there are following it regardless of how sporadic and annoying it is.

DS: Are you not worried that this log production schedule harms the narrative?

JHL: Oh, there's no doubt it hurts the received narrative for those who have been kind enough to try and follow the story as each chapter is published, but it won't harm the narrative itself, in the end. I see a story as a journey for both author and audience.

My drawing and writing ability will (hopefully) continue to improve as time goes by, but the change is gradual enough that the reader shouldn't notice. It happened in Jar of Fools, and hopefully it will continue to happen for the rest of my working life. Otherwise, I don't see the point. DS: Have you every visited Berlin? If you have, what was your impression of it then and how did it compare to your preconceptions about it?

DS: Have you every visited Berlin? If you have, what was your impression of it then and how did it compare to your preconceptions about it?

JHL: I visited Berlin for the first time in early 2000. I was very apprehensive, worried that the actual place would feel so different from my imagined city that the whole project would be disastrously compromised. But thankfully, the parts of old Berlin that still exist, and the feel of the city, were very much in keeping with my internalized concept of the city. It was a wonderful and strange experience.

DS: Apart from suggesting we read Berlin, can you describe what that concept is for us?

JHL: Yikes, I'm afraid I can't. It's something that I really can't articulate by any means other than what I'm trying to do with words and pictures. It's something big and sprawling and dense, only small pieces of which I'm struggling to delineate. This is an area, for me, where the word and the picture together are far more effective means of expression than words alone could ever be.

DS: Is this range of expression the secret of comics that the great mass of people don't realize?

JHL: Yes, it is. And they can't be faulted for not realizing it, because there have been scant examples of real breadth or depth in comics to date. Those artists who pushed the pre-exisiting boundaries (Chester Brown, Ben Katchor) have had relatively little visibility, and will simply be seen as post-modern anomalies ("Look what this genius did with the old goofy comic book!") until a larger body of such work exists.

DS: Berlin in color, why not?

JHL: Comics is already a highly complex form, and the addition of color to Berlin would only serve to multiply its complexity. I think it is the rarest of cartoonists who can execute a color comic while retaining the operative magic of the medium. Chris Ware is the best example of someone who can do that. My skills with color certainly do not begin to approach that level of mastery, and so I think it best for me to steer clear.

Plus, it would reduce my already-glacial rate of production to a near full stop!

DS: Would you ever consider letting a colorist have a go at it?

JHL: It's nearly impossible for me to imagine. It would drastically change the reading of the book, and would most likely result in creating a greater distance between the reader and the work. The way the white of the page works in Berlin -- as a lubricant and cohering element, as free room for the reader's imagination to operate -- would be pretty much destroyed. I guess the answer is, "No."

DS: Have you ever collaborated on creating a comic?

JHL: Yes, on several occasions. Catchpenny Comics, the first book I put out through a publisher, contained stories written by other people and drawn by me. There are a number of other forgettable (if not detestable) examples. I've only had truly happy collaborations with two people: my old art school friend Jake Austen, who wrote six or seven episodes of The Secret Three a kids' serial for Nickelodeon Magazine, and Ed Brubaker, with whom I collaborated on The Fall, which will be published this month in the US.

DS: If yes, how did you find that process?

JHL: The bad collaborations are always the ones wherein the writer doesn't understand the second thing about comics, and so has no idea how to write for the medium. Most writers for comics put the words first and are nearly completely ignorant about the most basic ideas, like "Show, don't tell." Those experiences have been so frustrating that they have made me doubt the wisdom of collaboration. Especially with mainstream comics writers.

But, thankfully, the positive experiences have dissuaded me of that opinion. Working with Ed on The Fall was a great experience. We had a lot of push and pull, going back and forth, tempering the words to suit the pictures and vice versa. The end result is the best of what one could hope for in a collaboration: we brought out the best in each other and learned a lot from the experience. The Fall is just a straightforward crime/mystery story, but we put a lot of thought and effort into the crafting of it, and we're both very happy with the results.

DS: The characters in both Jar of Fools and Berlin don't seem to have much control over their lives. Do you think anyone has?

JHL: Our attempts to control our lives seem an effort to stave off the chaos surrounding us, to which we define ourselves in opposition. But I tend to believe that anything approaching peace can only be achieved through relinquishing control completely. At least that's when I personally feel the most free, the most happy in my own life.

I would argue, though, that most of the characters in Jar of Fools determine their respective fates by taking decisive action at some point in the story. In Berlin this dynamic is less apparent, but will become more visible as the story progresses.

DS: What comics have you read recently? Why did you like/dislike them?

JHL: I'm currently reading Safe Area Gorazde, by Joe Sacco, which is an extraordinary book. It's an incredible comic, but beyond that it is the most gripping and informative account of the Bosnian War I have come across in any medium. It does a better and more thorough job of conveying the specifics of that conflict and its attendant horrors than any television broadcast, newspaper, or book I have seen.  DS: If a film was made of your life, who should play you?

DS: If a film was made of your life, who should play you?

JHL: Oh my God. Um... Kate Winslet in drag.

DS: Are the people who call comics art out of their minds or what?

JHL: Yes I am.

DS: If someone bought two copies of Berlin, City of Stone, carefully took the copies apart and put the whole story on the wall of a gallery (The Guggenheim Museum in New York for example) would it be a good idea or not?

JHL: Bad idea. Reading a comic is an intimate experience, between the reader and the open book, up close and subtly interactive. I design my comics with careful attention to facing pages and page turns -- the physical structure of a book is integral to the storytelling. Each page spread is a little portal between the author and reader, and that close communication would be destroyed by putting the pages up on a wall. You can certainly read a comic that way, but it is robbed of much of its potential.

DS: The Seattle Institute of Fine Art list you as one of their instructors. What does this position involve?

JHL: I've taught several comics classes for kids and adults there. The kids ranged in age from seven to thirteen, and over the course of a five sessions they would write and draw a minicomic, of which each of them would receive a copy. The adult class was sort of Comics 101, concentrating on basic conventions and working methods. The adult classes still meet informally to keep up with each others' work. I'm not currently teaching, but hope to do so again in the future.

DS: They also comment that you have published your own "art comics." What does that term mean?

JHL: Not being very well-versed in the world of comics, they use that term in an effort to get across the idea that I do "adult" or "serious" comics, I think.

DS: If a student were to present you with their work, which consisted in some long legged near naked super heroin pushing her rear end into the face of the reader, asking your opinion, how would you react?

JHL: Well, it would depend on the circumstances, like if it was a nine year old kid or an adult. If it was an adult, I would try to discern his intentions and see if there was a way to steer him toward something more interesting. My comics classes are about how to make comics, though, and if someone wanted to make a T&A comic, I would just try to help them make the best T&A comic possible.

DS: My thanks to Jason for taking the time to answer my questions..

Berlin: City of Stones is due for release February 15th, 2001.

Related Links:

Related Links:Comprehensive profile at Drawn and Quarterly

His reply to a survey on inking techniques

Translatio of Jar of Fools

Review of Berlin

History of the Seattle comics scene

C.A.P.E. Headquarters

If you have a comment or question about Small Press then feel free to contact me