Viewpoint: "It Said So On TV"

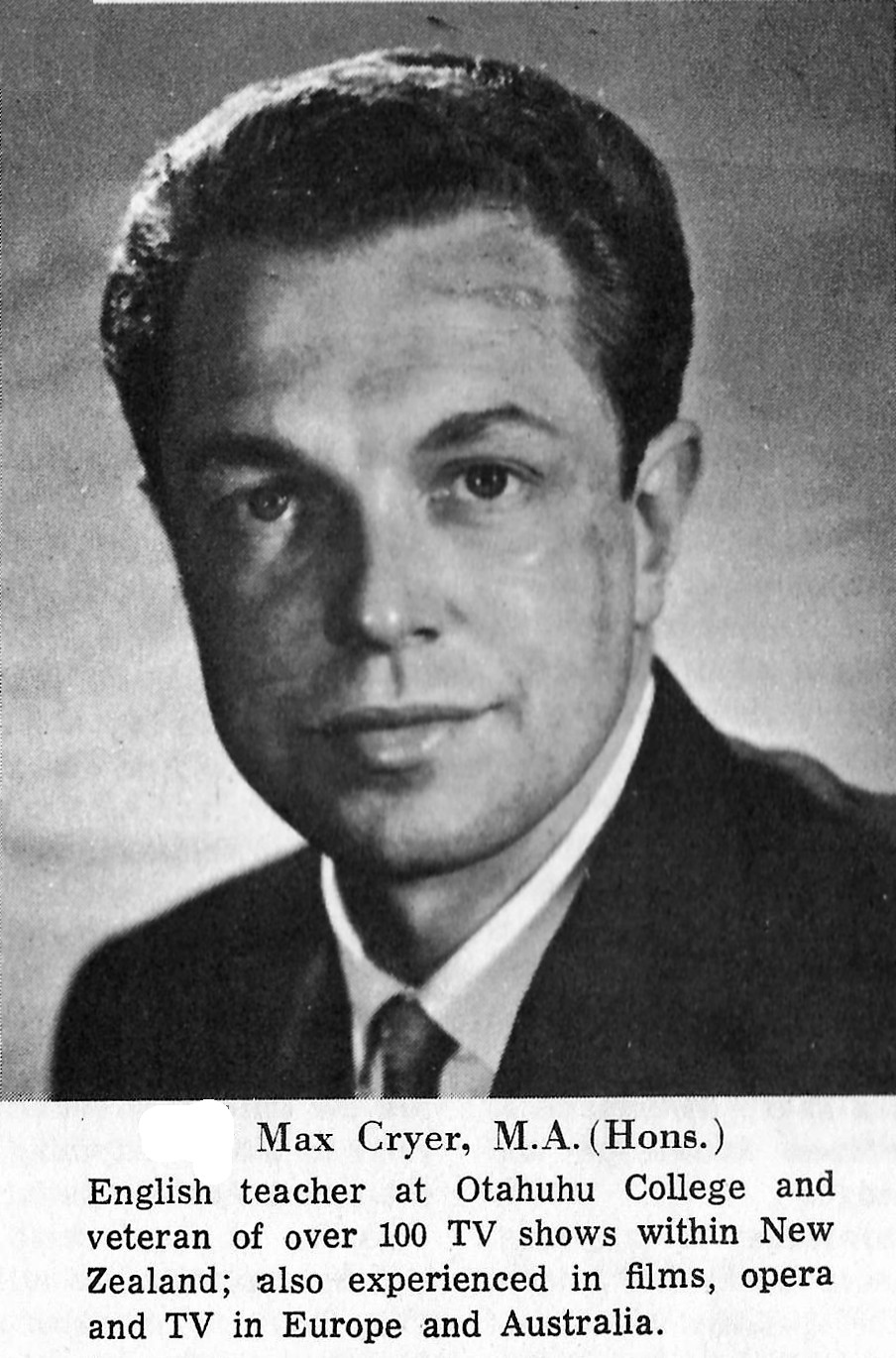

By Max Cryer, originally published in the New Zealand TV Weekly June 6, 1966

By Max Cryer, originally published in the New Zealand TV Weekly June 6, 1966

A new phrase has joined our children’s language- It said so on TV.

Not that this phrase is confined to children. You hear it at every smoko, sportsmeet and supermarket. But it is probably in the children that the habit will take the strongest root.

The question arises-how much do children learn from TV?

Quite a proportion of television time seems to be taken up with facts. Documentaries, news releases and quizzes are some. Many children react badly to these and are bored by something which “has no story.” The type of child who needs wooing into learning anything in the classroom, will probably have to be wooed into fact-gathering from TV as well.

But even the most resistant child will tend to pick up pieces of information from programmes he’s seen. He just can’t help it. Unless we enter a state of fascination akin to ecstasy, our minds must register a certain amount of what is fascinating us. And TV fascinates most children.

Sometimes, as in quiz programmes, the facts are deliberately laid out in an entertaining form which it is hoped people will enjoy. Learn from as well.

Sharp Distinction

But there is a sharp distinction, to my mind, between knowledge and general knowledge.

To have knowledge of anything, you must possess a certain amount of fact. But the possession thereof doesn’t automatically make you a knowledgeable person. The child who watched Martin Chuzzlewit or every episode of The Great War and can name characters, dates, times and events from these, has a good general knowledge of the two subjects maybe. But he cannot be said to he knowledgeable on the import of war or Dickens’ contribution to literary style, just because of this.

I was a schoolfellow of a quite famous quizkid who couldn’t be A faulted on the length of the Amazon or the birthdate of Catherine the Great. Yet he was more or less a social outcast because the boys said of him that he was just a fool.

And he was.

It is quite clear, however, that the child who does, know the details of Chuzzlewit and the chronology of war learned these from TV. Learned them easily too. Nobody is in any doubt about the ease of the medium for put- ting across information. But here arise two points.

Fact or Fiction

Can the child tell which is fact? And how much effort has gone into presentation so that it will be easily assimilated?

The first of these problems is one that frequently appals me. TV content is roughly in three categories- fact, fiction, and advertisement (some strictly entertaining or musical programmes do not fall into any of these categories, but again do not convey anything which could be regarded as fact).

Some children seem quite unable to see the difference between these, and refer to almost anything they saw on the screen as if it was fact.

As far as the factual programmes go, there is not much misgiving about this. TV is far too exposing a medium for anyone who is claiming to give out facts, not to have them checked, double checked and re-checked before going on air. The only danger is that imported programmes often allow opinion to mingle with the fact, and our children are not used to this. (In other countries there are newsreaders, and also news commentators, the latter giving their opinion, interpretation, and even advice regarding news items they have just read.

New Zealand news readers are not allowed to do this, and except for a couple of radio programmes and a tentative small-scale step in this direction on TV, news commenting is a system which the NZBC is as yet only exploring, to bring it in line ex entually with overseas practice.

Nevertheless they still import radio newsletters and the occasional TV programme which does introduce Opinion into the fact.)

Doubtful Information

The real horror occurs when our children start to pick up pieces of doubtful information from TV programmes which are fictional, or planned by an advertiser.

Because a man puts on a white coat and acts the part of a doctor, or a teacher, he is nowhere near being one. The characters who shout hatred in playing the parts of antisegregationists, are merely mouthing words the scriptwriter wrote. But many children in a muddled kind of way recall that the TV screen, which often puts out authoritative facts, endorsed by their parents and teachers as being so, sounds just as authoritative in its other offerings, part of which they remember, but don’t realise are fairytale.

And even worse, the planned Godvoice of advertising reaches (as a result of expensive research) into the child’s awareness. It’s good for your hair,

a boy told me about a certain hairdressing, it said so on TV.

I told him it was a lot of rot.

A teacher of girls assures me, however, that the female child is inclined to be more sceptical about advertising than her brother, at least over household products. Mum likes to test them for herself,

is the word.

Mum has to buy them first to do this.

Remember that the manner in which both the advertising persuasion and the 23 inch fairytales are presented is usually very glossy. They are easy to absorb because they are beautiful. Exquisite looking people with smooth pre-written conversation, the world’s most expensive dressmakers and architect designed bookends, all combine to peddle off stories which were "suggested by or based upon” an idea of someone else, and finish up giving a completely false impression of the American domestic help situation, the New Zealand Christmas or British brass bands

These are the items which our children are quite at liberty (as indeed anyone is) to accept as entertainment. But not as any particular kind of knowledge. Except perhaps on how to be an efficient TV producer.

A Challenge

It is this very glossiness of presentation which faces the TV educationalist as a challenge.

There are, as we said, many children who don’t like programmes without a story, or a star. But these people will enjoy documentary material, or quiz material, if it is as pretty to watch as their fiction favourites.

And documentaries often aren’t.

If we think in terms of children, and make the programmes look pretty, this looks a bit like wooing. And it is. How else? >p>One thing TV has done for everyone, it has made them used to slick presentation.

Even the trash is neatly coiffured and carefully timed and manicured to the last recorded laugh. Put on a less-thvan-perfect local show and listen to the snide comparisons.

This is one of the problems of bringing TV right into the schools and having educational TV programmes.

The lessons must be presented well or no-one will absorb them. It must be the right person facing the camera or he will look foolish. The visual demonstrations must be well-oiled and the camera movements must not be naive.

To a child, TV means neat, painless organisation. He’ll absorb general knowledge, sure, so long as he’s not scornful or bored by the way its being done. A pound of bacon cooked by a hotel chef is no more platable but much more appealing than when cooked badly.

Teachers and TV

Nearly all educationalists dealing with TV agree that there will have to be a teacher in the room if televised lessons occur. The screen will teach the facts, the teacher will bind them together into knowledge. And probably in the long run, the child who spends a lot of time in communion with the printed page may have the fullest knowledge. He is in control of the medium. The book does not control him.

It's not much use trying to utilise the subject matter of home TV during classroom time. There isn't much consistency-some children still don’t have TV at home and others might not have seen it. If it is ever done, then it is an extension of the screen- first-teacher-later technique mentioned before.

Curiously, though the eye is what attracts children to TV, they often learn their facts from the sound rather than the sight. Apart from obvious visual things, many quiz programmes and news-readings are basically radio programmes, just put on TV.

I’m sure that TV is a magnificently effective means of picking up pieces of knowledge. Sporadic facts, and maybe some more broadly landscaped ideas. And it does more than that. TV has brought lively aspects of the world into quiet country places, and also broadened the outlook of many narrow people who have learned things about Vietnam and A. J. Cronin they might otherwise never have known.

But for children, general knowledge is not quite the same as the general developed education aimed for in this country. While TV is excellent at one, it can never replace the other.

Comments powered by CComment