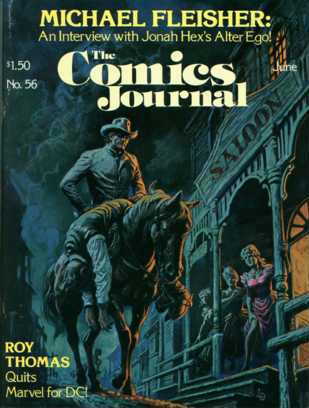

Comic Journal #56, June 1979

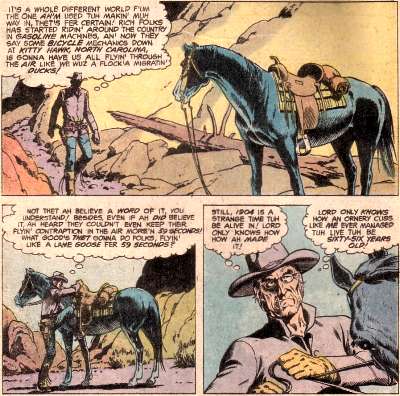

The cover painting is by Luis Domingue, and was originally scheduled for use on the fourth issue of DC's Digest Comic Jonah Hex and Other Western Tales, but the title was cancelled with #3.

This magazine contains a very lengthy and informative interview with Michael Fleisher, excepts of which follow...

THE BLESSED LIFE OF Michael Fleisher

An Interview with the Man Who Stuffed Jonah Hex

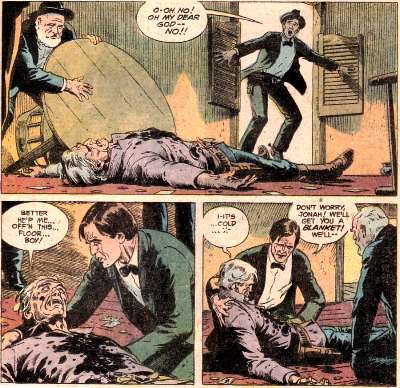

Michael Fleisher has a violent imagination. It has, during the past decade, brought us the sight of a man being turned into a block of wood and then sliced up by a buzzsaw; the bloodied body of Jonah Hex stuffed and put on display in a Wild West show; and the assorted killings, maimings, and dismemberings of countless protagonists, antagonists. and incidental characters.

This inventively gruesome streak in Fleisher's fiction has earned him no small degree of notoriety among fans and pros alike. But while a lot of attention has been directed to Fleisher's violent comics stories, what is perhaps his greatest contribution to the field has received comparatively little notice.

The Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes consumed seven years of Fleisher's life. With the help of his research assistant, Janet Lincoln, he compiled and wrote the ultimate reference guide to the major comic book heroes. The sheer enormousness of the task is awesome. Fleisher read and took full, detailed notes on every single Batman story published between 1939 and 1966. Then he did the same for Superman. And Wonder Woman. And Captain Marvel. And on and on and on until he had researched 22 super-heroes and super-hero groups in all.

When he finished. he had written over two million words. The three volumes published to date comprise only about 1 half of the full encyclopedia. The remaining portion covers Captain America. Captain Marvel. Doctor Fate, both Flashes. both Green Lanterns, both Hawkmen, The Hulk, The Human Torch, Iron Man. Plastic Man, The Spectre. The Spirit. Starman, and The Sub-Mariner. Fleisher also has notes on Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four, but has not written manuscripts on them.

Somewhere along the line. he began actually writing comics. in addition to writing about them. While serving a brief stint as Assistant Editor to Joe Orlando. Fleisher was given his first crack at a series: The Spectre. Today. five years later. The Spectre is still one of the two characters that leap to mind when Fleisher's name is mentioned. Even though the series lasted only 10 issues, it firmly established Fleisher's reputation as a writer of powerful, gut-wrenching stories.

The other character people associate with Fleisher is Jonah Hex, which he began writing shortly after beginning on The Spectre. But even more than The Spectre, Fleisher has turned Jonah Hex into "his" series. By gradually weaving the tale of Hex's past into the series', Fleisher has meticulously peeled back layer after layer of the character, defining him so 'sharply and completely as to effectively prevent any other writer from violating the legend of Jonah Hex that Fleisher has established in his own mind. That process culminated in the landmark Jonah Hex Spectacular, in which Fleisher had Hex murdered, then stuffed like a hunting trophy and put on public display.

With the establishment of Hex's

death, Fleisher has gained complete control over the bounty hunter's

life, to a degree unequalled by any other writer on any other comics.

character. In a medium where virtually any character can be chosen

for a complete revamping (in response to declining sales or simply at

the whim of a writer or editor), Fleisher's achievement of precluding

such interference is a tribute to the thought and care he has

invested in the series.

With the establishment of Hex's

death, Fleisher has gained complete control over the bounty hunter's

life, to a degree unequalled by any other writer on any other comics.

character. In a medium where virtually any character can be chosen

for a complete revamping (in response to declining sales or simply at

the whim of a writer or editor), Fleisher's achievement of precluding

such interference is a tribute to the thought and care he has

invested in the series.

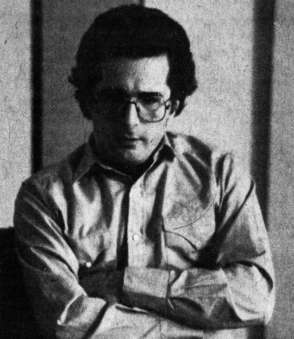

I have been fascinated by' the work of Michael Fleisher since I read his first Spectre story in 1973. I read his work for the short-lived Atlas Comics line in 1974-75 with great interest. His stories are frequently horrifying in a fascinating way. They can be shocking, repelling, amusing, even poignant. Yet-the man behind those' tales is not violent at all. He is, in fact, a serious, soft-spoken writer with an intense commitment to his chosen craft.

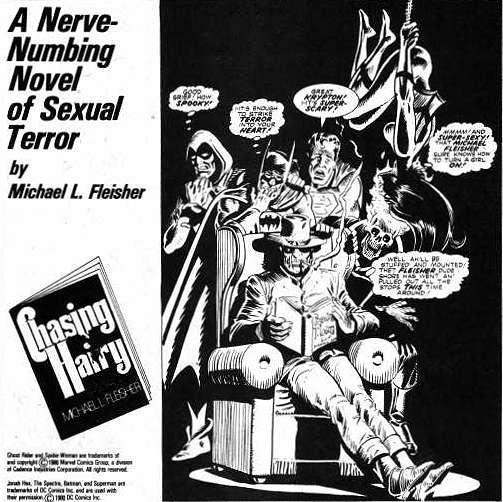

Recently, he began freelancing for Marvel, while continuing to write for DC. Last summer. St. 'Martin's Press published his first novel, Chasing Hairy, "a novel of sexual terror. "

Fleisher was born in New York City in 1942 and grew up there. He

lived in Chicago for eight years and spent a year in Mexico. Today,

he lives in a West Side apartment near New York's Central Park, where

this interview was conducted, February 9, 1980. Also present was

artist-photographer Bob Smith.

-MICHAEL CATRON

This interview was transcribed by Kim Thompson, and' edited by Michael Fleisher and Michael Catron.

CATRON: Comics absolutely fascinate me. I started out as a fan of the super-hero and only later began to develop an appreciation of the medium itself-the storytelling, the integration of words and pictures. Have you given any thought to why comics appeal to us? What is it about comics that make them such a neat medium? '

FLEISHER: I don't know the answer to that. Comics are a form of fairy tale. They touch very deep-rooted psychological stuff in kids, and they touched that in me. Even though I had left comics behind at an age when most people do leave them behind, they had played an important part in my childhood and when I rediscovered them I remembered that old excitement. I don't know if what I'm abut to say is very meaningful, but when I returned to comics, I returned not as a child any longer-that is, as a child I read comics and I enjoyed them" but as an adult I write comics and as an adult I wrote The Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes-those are not children's things to do. 's an incorporation of that early childhood pleasure .wholly new, adult level.

CATRON: What comics did you read as a child?

FLEISHER: I read comics from the time I was six or seven to the time I was 14--about 1948 to about 1956. I read everything that had Batman in it and everything had Superman or Superboy in it. So I had a very run of Batman and Detective and World's Finest and Superboy and Action and Adventure. But I used to read a lot of other comics. I don't think I avidly collected anything else. but I read a lot of other things that were coming out: I remember reading Mighty Mouse and The Fox and the Crow and I read Archie and I read a whole bunch of different westerns. The ECs used to frighten me, but I did read an occasional EC. Every now and then I'd go to the barber shop to have my hair cut and there would be an EC there and I'd read it-but I didn't read them regularly and I did not collect them.

CATRON: Did you write your own comics as a kid?

FLEISHER: No. And I was not a fan. I wasn't aware there were fans. When I was 14, I took my entire collection of comics, which numbered over 2,000, and I sold them to a junk lady on Third A venue for a penny apiece. So 1 made about $22. That was in 1956; I didn't look at a comic again until 1969.

CATRON: That was when you began researching The Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes?

FLEISHER: Yes. And when I started reading the comics, I was really blown away by them. I started with Batman. Batman had been my favorite character when I was a boy and I just loved him. I don't really know how to describe this in words: I wasn't a fan then and I'm not a fan now, but I was really swept away by these comics that I hadn't seen in many years. And I was convinced that this was really a great American treasure that almost everyone else was overlooking. You also have to remember that in 1969 there really had been no books on the comics, or there had been very few. Even now, what's appeared has been mostly picture books. My idea for the book I wanted to do was not a picture book-it was an encyclopedia. And I guess that reflects the fact that I'm a writer and that I have literary interests.

CATRON: Yes. You earned your Ph.D in English at the University of Chicago. Did you do a lot of writing in college?.....

.....in one

panel of my story. But people who are afraid of what's lurking inside

them can't do that. They can't walk that mile. And I think that will

hold them back from true literary or artistic achievement.

.....in one

panel of my story. But people who are afraid of what's lurking inside

them can't do that. They can't walk that mile. And I think that will

hold them back from true literary or artistic achievement.

CATRON: I'd like to talk In general terms about writing comics.

FLEISHER: Okay, I'd like to talk about that.

CATRON: I want to talk, first of all, about the relationship between writer and artist. Which is probably the most important relationship. You've worked with a number of artists. What determines in your mind how good an interpretation you get from any given artist on your script! You read your story after it's been drawn and you evaluate how close the artist came to giving you what you wanted. What makes for a good Interpretation of your script, and what makes for a bad interpretation of your script'!

FLEISHER: Well, first of all, some artists are more skilled than others, because God made some people better artists and better writers than He made other people. But then you want an artist who identifies with what you've done, 'an artist who, really can identify 'with your vision and live with it and add something to it. What sometimes happens, unfortunately, is that the artist is really at war with the vision of the writer.

I'll give you a specific example of what I'm talking about. I did a story in which a woman whom Jonah Hex loves dies in his arms and Jonah Hex in the first moment. of grief kisses her on the mouth after she's died. I thought it was a very powerful moment in the story. Now the artist was very uncomfortable with this. He took the' story and brought it in to the editor-he'd written a whole new ending for it. In his ending, Jonah Hex picks up the girl, carries her to the, graveyard, and buries her, or something. Fortunately, in the case of that particular story the editor insisted that the story be redrawn to meet the requirements of the original script.

But I use that as an example because it was a case where the artist was clearly made uncomfortable by what was in the script. In fact I'm told he said he thought my ending was disgusting. Now again there are stories which, if I were an artist, I wouldn't want to draw. I'll give you a good example: I'm made very uncomfortable by cruelty to animals in stories Now, I'm not saying that people shouldn't be able to write stories that have cruelty to animals in them. I just mean they make me uncomfortable. I don't like to read them and I don't want to have to write them. So if an editor says, "Listen, we're going to have a story where the hero kills a pack of wolves," I wouldn't want that in one of my stories. It just makes me feel queasy and uncomfortable for reasons that are personal and I don't want to have to do it. But neither do I want to take on the job and do it badly. Do you understand?

So if an artist looks at a story and feels that

he can't really go with the story, I think it's better for the artist

not to do the story. Now maybe that's asking too much-I mean, this is

a business, and you have to make a living, so maybe it's asking too

much-but that does happen in comics, especially with the stories I

do, which often seem to make people uncomfortable. .

So if an artist looks at a story and feels that

he can't really go with the story, I think it's better for the artist

not to do the story. Now maybe that's asking too much-I mean, this is

a business, and you have to make a living, so maybe it's asking too

much-but that does happen in comics, especially with the stories I

do, which often seem to make people uncomfortable. .

CATRON: Didn't you write a Jonah Hex story in which the artist drew something different from your art directions, which then led to one of those bizarre encounters with the Comics Code'!

FLEISHER: Well-yes. Now in that story, as it was written, some bad guys beat up Jonah Hex and they place his hands on a hitching rail so that he is posed the way you'd be posed if a policeman were searching you if you were leaned up against a police car. His hands are gripping the hitching rail. Then the script called for the bad guys to take railroad spikes and hammer them through Jonah Hex's hands into the wood of the hitching rail. As a result, his hands are all bandaged and he can't use his sixguns for the duration of the story. Now, the artist took this story and he changed the position of Jonah Hex so that his back was to the hitchingpost. Now it became a crucifixion. Now the spikes were being driven through the palms of Jonah's hands and the scene resembled a crucifixion. The Code said it was sacrilegious to have a crucifixion and therefore said we could not use the spikes. Not because the spikes were so brutal, you understand, but because religious people might be offended. By the way, I thought that was just incredible reasoning. What the Code said to us was that only Christ could be crucified. By that reasoning, you presumably couldn't show the two thieves who were crucified alongside Christ in a 'comic book because they weren't Christ either. Be that as it may. I never meant the scene to look like a crucifixion. That was a case where the artist imposed his own vision on the story in a way that, in my view, ended up doing damage to the story.

Now let me give you one other example. I write

The Ghost Rider for Marvel and I think that Don Perlin is an

extraordinary artist. We work closely together and we, have a very

excellent rapport. The Ghost Rider is an example of a situation in

-which both artist and writer share the same goals. That's not to say

that every story is a perfect story, but when I want something scary,

Don wants it to be scary too, and it comes out looking scary. When

Johnny Blaze changes identities, it's scary-I think it's the scariest

transformation from civilian to superhero-if you'll excuse the term

super-hero-of any character in comics. So it's a case where there's

real unanimity of purpose between writer and artist. When that

doesn't exist, the story invariably gets compromised.

Now let me give you one other example. I write

The Ghost Rider for Marvel and I think that Don Perlin is an

extraordinary artist. We work closely together and we, have a very

excellent rapport. The Ghost Rider is an example of a situation in

-which both artist and writer share the same goals. That's not to say

that every story is a perfect story, but when I want something scary,

Don wants it to be scary too, and it comes out looking scary. When

Johnny Blaze changes identities, it's scary-I think it's the scariest

transformation from civilian to superhero-if you'll excuse the term

super-hero-of any character in comics. So it's a case where there's

real unanimity of purpose between writer and artist. When that

doesn't exist, the story invariably gets compromised.

CATRON: I want to talk more about Don Perlin and The Ghost Rider later, but before we do, can you compare what it's like working with different editors'! I.think the major editors whom you've worked with have been Joe Orlando. Larry Hama, Ross Andru, Denny O'Neil, and Jeff Rovin.

FLEISHER: I think the important thing-tell me if this is not the answer to the question you're asking--I think the important thing is that in order for really good work to emerge the writer and the editor have to have a genuine rapport. Larry Hama and I, and Joe Orlando and I, tend' to really like the same things. Whenever I proposed an idea to Larry Hama, if' I was enthusiastic about it, usually he was enthusiastic about it too. And the same was true with Joe. It's Important to have that rapport because if the editor and writer don't like the same kinds....

...inspires a new person, who in, turn does a bang-up job with it.

CATRON: I wanted to ask you something about Scalphunter, and this is lust to get the record straight. In the final Weird Western with Jonah Hex, I believe, there was a comment on the letters page to the effect that there was a new hero coming out who had been created by Joe Orlando and Sergio Aragones, and then the -next issue we have Scalphunter, and of course you created Scalphunter, so I was wondering what happened to that character...

FLEISHER: Well, I think what happened was that Jonah Hex was going to go into a comic book of his own and Weird Western was going to be dropped, and Sergio was at the office and he said, "Why should you drop a title that's been selling well for years? You should come. up with something new for it." And I don't even remember what they came up with. I don't really think they came up with much of anything, an idea for an Indian, maybe. I think one idea that was thrown around between them' was an Indian who would live in an abandoned 'fort. Another idea was an Indian who operated a ranch. I mean. it was extremely vague. I was called in and 1 said, "Look, I'd like to come up with something and think out these things." I was given a lot of' freedom. The people at DC, I have to say, have always given me a great deal of freedom. So I went home and I invented Scalphunter. I produced a lengthy character description, and also a plot for the first, story, and my proposal was evaluated at bc, and it was accepted, and I started to write it.

CATRON: You're involved in discussions now about a new western character[1], right?

FLEISHER: Yes, but I'm not at liberty to discuss it.

CATRON: When will it be coming out?

FLEISHER: I don't know the answer to that. It's going to be written soon, and I don't know how long the normal production takes. You probably know that better than I do-.four months, five months, six months. I'll tell you, you mentioned this once before in a conversation we had, that I'm in a kind of peculiar -position in that I write for both DC and Marvel. I enjoy that very much, I'm very happy that I write for Marvel as well as DC, but it puts me in the position of having to be really careful that I don't compromise Marvel's ideas or DC's. I'm very careful, if I pick up some information at Marvel or know something about something that's forthcoming, never to mention it outside Marvel. And if I'm at DC, the same principle holds true.

CATRON: All right. When you're doing a script you have to think in visual terms. I have been told this man)' times. Can you explain what that means?

FLEISHER: I don't get a chance to talk about this kind of thing much. I'd be happy to talk about it but I think I'm something of a maverick, and I think I'll say jolting things. I'm interested mainly in the stories. I don't know much about art, and I don't know anything about the techniques of art, and I don't know-I'm not really a good critic of the art. I only know when the art has captured what I wanted to do in the story. That's my basis for criticizing the art. If I wanted a scene to be scary and it's 'not scary, I feel disappointed. If I want something to be exciting and it's boring, then I criticize. But I don't know a lot' about the art. I'm interested in the stories and I believe the stories proceed from conflict between characters or within characters. I'm interested in the characters. I approach a story from the point of view of the characters and not from the point of view of the locations. I know that in comics, as in a lot of movies, the idea is to pick out interesting locations. But I think that's less important than it's made out to be. And anyway, for me, it's secondary. Do you understand what I'm saying?

CATRON: Yes, I understand what

you're saying, but I'm still thinking of some really nice visuals,

that I've seen in your work. There's a scene where Jonah goes into a

bar, and everyone there leers him because they know he's Jonah Hex,

and they think he's responsible for tile massacre of Southern troops

at Fort Charlotte and they all desert the bar. They say-

CATRON: Yes, I understand what

you're saying, but I'm still thinking of some really nice visuals,

that I've seen in your work. There's a scene where Jonah goes into a

bar, and everyone there leers him because they know he's Jonah Hex,

and they think he's responsible for tile massacre of Southern troops

at Fort Charlotte and they all desert the bar. They say-

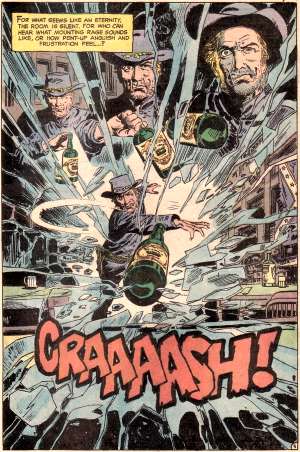

FLEISHER: He throws a bottle in the mirror...

CATRON: He throws a bottle in the mirror. I thought that was a very powerful visual scene and I credited that to you rather than to the artist. I

FLEISHER: Thank you.

CATRON; There, was the whole thing in the Ghost Rider, where he rides up the cooling tower of a nuclear power plant. "

FLEISHER: Well, let me Say this,: Maybe there are just certain things that I do well, naturally and just don't.' think about consciously. I hope that doesn't sound overly conceited. For example, I've been told that the pacing of my stories is very good. Forget whether it's true or not for the moment-people have told me that- "Gee, your pacing is very good." But I've never thought about pacing in, any story, I ever wrote. I never even heard the term until after I'd been involved in comics for five years. I never think about it. If I do it well, knock on wood, I do it well because I have an inner feeling for how a story should be constructed. But I never think about that.

I think about the characters and what the conflicts are in the story and then I try to make the story exciting. ' And if I've been able to produce art directions for exciting visual images, maybe I'm just able to do that. Maybe that just happens when I think about a story. The only writer whose thought processes I know anything about is me, and when I'm thinking of a story, or writing a story, I'm seeing the action in my mind. l think every ,writer is. But I'm seldom aware of making any special effort to be visual. When I wrote my novel. Chasing Hairy, which is literary and not visual, I devoted the same kind of thought to it as I devote to a comic. Now it is true, I guess, that having conceived of a plot for a comic book story, I might make certain improvements in an effort to be more "comic book" visual. In a serious novel two people might have an argument in a living room. In a comic book you might want to have the argument take place in a circus or some other highly visual location. Because comics really are about spectacle, and you'd want to set your scene in a visually more spectacular place But I don't devote a lot of extra thought to that. Mainly it's the character conflicts that matter to me.

CATRON: Well, in the beginning when you were writing the Spectre. the

first two or three Jonah Hexes, ' a great many mystery stories,

credit for script continuity

was given to Russell Carley. Can

you tell me what he did?

FLEISHER: Yes, I can. Russell Carley is a fine artist, a painter, who's a very close friend of mine, 'and when I 'first began to write comics regularly. I really had no experience in coming up with the plots for example, or in breaking down the stories. Those were both intimidating things for me to do. So Russell and I would get together and we would work out a plot together. We'd sit together on a Saturday afternoon and we would throw ideas back and forth and we would produce a plot. And when I'd gotten the plot okayed, Russell would take the plot and he would make a breakdown of it-that is, he would take sheets of paper and divide them into panels, and he would describe in each panel, very briefly, what was to take place, and then he would give me these pieces of paper and I would write the script. When we started out we wanted to say, "Story by -Michael Fleisher and Russell Carley," but Joe Orlando felt that we should distinguish between what he did and what I did so we said "script' by Michael Fleisher," and there was no standard title in comics for what Russell was doing, so we made up a term,. In retrospect it was a confusing term, and no one....

...the vampire. And how about the old chestnut In which the bad guy commits a murder to get his mitts on the succulent chick only to have her turn into an old hag before his very eyes at the bottom of the last page?

So I decided to write some stories that were really scary, not just pretend scary. And that meant doing a lot of thinking about what people are afraid of and what makes certain kinds of situations terrifying. The story I did for Dark Mansion about the street corner Santa who lures young children to his skid row boarding house and then hangs them from the ceiling by an electric light cord now that was scary. And the story about The Spectre and the mannequins that come to life and slaughter people. that was scary too.

Mannequins are pretty spooky anyway. You know, sometimes, from a distance, in a crowded department store, it's hard to distinguish them from the customers. And they're all around you in a department store, posed in their eerie poses. Lifelike but also deathlike at the same time., That scene in the Spectre story in which the department store mannequins spring to life and start murdering the patrons in the store for no apparent reason was one of the scariest scenes I. ever wrote for a comic.

I think many of those stories I wrote are terrifying because I developed a canny knack for taking everyday things, things we all take comfort in and trust-like butterflies and Santa Claus' and toy teddy bears-and turning them into creatures of horror and violence. Anyway, at least I tried. Many of the other mystery writers didn't.

CATRON: Okay. I want to ask you about the second of the three favorite stories you mentioned, "The Last Bounty Hunter." There's no question that that was a powerful and disturbing story-we witness the murder of Jonah Hex at the age of 66. Then his body is stuffed and put on display.

Larry Homa, who was your editor then, once told me that he ran into a lot of flak getting that story into print.

FLEISHER: I don'~ think there's anything special to

ten, really. We needed a story for the Jonah Hex Spectacular and I

came up with a plot about the last days of Jonah Hex. I presented it

to Larry, Larry liked it. I wrote the script. It was assigned to an

artist and eventually it came out. I didn't think of it as a story

that we'd have a hard time doing. Larry fought to be able to use the

artist he wanted to use on that story. Russ Heath, who did a simply

brilliant job on it. It was really only after the story came out,

that I became aware that if it hadn't been for Larry Hama, there

wouldn't have~ been that story.

FLEISHER: I don'~ think there's anything special to

ten, really. We needed a story for the Jonah Hex Spectacular and I

came up with a plot about the last days of Jonah Hex. I presented it

to Larry, Larry liked it. I wrote the script. It was assigned to an

artist and eventually it came out. I didn't think of it as a story

that we'd have a hard time doing. Larry fought to be able to use the

artist he wanted to use on that story. Russ Heath, who did a simply

brilliant job on it. It was really only after the story came out,

that I became aware that if it hadn't been for Larry Hama, there

wouldn't have~ been that story.

You see, I have the idea that if I want to write a story, they ought to let me write it. I don't think about that when I come up with a story. I don't gird myself for the battle. I go in there, I'm enthusiastic, I want to write it, I expect-I don't mean to sound arro.rant, but that is how t feel about the stories: that if I have an idea I really want to do, I should just be able to do it.

When it came out, that story was read by a lot of people. There are

certain stories that wind up on everyone's desk somehow. I remember

one story like that was a Steve Gerber Man-Thing story called A

Candle for St. Cloud.

It was one of the very best stories I've

ever read in a comic, and when that story came out, you'd go to DC,

and everyone would be reading that story. "The Last Bounty Hunter"

everybody read, and people whom I didn't know well at the time,

people from Marvel-I wasn't yet working at Marvel-came up to me and

told me how much they liked the story. But even when they said they

liked it., they always said something else that made it clear to me

that if they'd been in charge, the story wouldn't have been done. One

person said. l wouldn't have thought you could kill a character

and have it be okay. but you did it, and it worked!

And I would

think to myself, "Well, what about that? If I'd gone to that person

about the story, would he have been wiling to let me do it?" Or

another person said. "Y'know, it was a really great story, it's too

bad it happened to be Jonah Hex-maybe you should have written it

about some other western character-a new western person, for a

one-shot story."

So I, think that it took-I

didn't really appreciate it at the time. I ran in with the story and

I said, "Larry, there's a story I have to do, it's going to be

incredible." And at the time I just took it for granted that I would

be able to write it. But in retrospect I can see that if Larry hadn't

believed in me and believed in that story, if he hadn't been willing

to fight for the story in the organization-remember. I'm a

freelancer. I walk in and out, but editors have to live there-if he

hadn't been willing to fight for the story, if he hadn't been willing

to find the artist he wanted and really nurse him through the project

and get it done on time, that story wouldn't' have been published.

And I think it's a marvelous story.

So I, think that it took-I

didn't really appreciate it at the time. I ran in with the story and

I said, "Larry, there's a story I have to do, it's going to be

incredible." And at the time I just took it for granted that I would

be able to write it. But in retrospect I can see that if Larry hadn't

believed in me and believed in that story, if he hadn't been willing

to fight for the story in the organization-remember. I'm a

freelancer. I walk in and out, but editors have to live there-if he

hadn't been willing to fight for the story, if he hadn't been willing

to find the artist he wanted and really nurse him through the project

and get it done on time, that story wouldn't' have been published.

And I think it's a marvelous story.

CATRON: I think Larry knew that he had a story from you that was worth fighting for.

FLEISHER: I'm not a modest person. I try to be realistic because if you're not realistic then you can't grow and learn. But I'm certainly not a falsely modest person. I think "The Last Bounty Hunter" is a very fine story; I think it's a landmark story. I'm very proud of it. And I'd like to say now, in case you don't ask me, that I think this whole business, that whole taboo against showing the death of the hero, is just bullshit. When a person reads a Superboy story, he knows that Superboy is going to grow up to be Superman doesn't he? And it doesn't spoil the suspense of a well-written Superboy story. Because suspense and excitement and fear for the characters' lives is not based on what you rationally know is going to happen. It's based on the ability of the writer and the artist to draw yon into their world.

I saw recently-not so recently-on TV a movie called The Lincoln Conspiracy. Maybe it wasn't a great movie, but it is suspenseful. It's about the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. And you watch the movie and you find yourself hoping that, just this once. John Wilkes Booth won't get into the president's box to shoot Lincoln. And when he does shoot Lincoln, you find yourself hoping that just this once. President Lincoln really won't die a couple of hours later. And that has to do with your emotional investment in the event, and not with what you rationally know is going to happen. When I do a flashback in which Jonah Hex is a young boy and he's menaced, people feel the menace, even though they know he's going to grow up to do other things. I think that those fears people have of doing unconventional things are really very foolish.

CATRON:

"The Last Bounty Hunter" was a significant story in several respects.

One of the themes that you handled very well was the last days of the

Old West-the civilizing of the frontier. Jonah Hex was a bounty

hunter. Yet as tine went on, there was less and less need for bounty

hunters.

CATRON:

"The Last Bounty Hunter" was a significant story in several respects.

One of the themes that you handled very well was the last days of the

Old West-the civilizing of the frontier. Jonah Hex was a bounty

hunter. Yet as tine went on, there was less and less need for bounty

hunters.

And I think Hex had come to realize that a new age was dawning and the 19th Century lifestyle he was living wouldn't work in the 20th Century-you sprinkled the story with references to the rapidly encroaching technology of the 20th Century. How did your idea for this particular story originate?

FLEISHER: Well, the first idea I had was to do a story about Jonah Hex being old. I've been trying to get DC to, let me do a whole separate series about Jonah Hex as an old man. I'm not having any luck. But that was my idea to do a story about Jonah Hex in his 60s. The idea that he would die came later. It came soon afterward, but it came second. And 1 knew that I'd already established, at least in my own mind, that Jonah Hex was' born in 1838. So I said, "Gee, 60s, what year wou1d that be?" and I found myself in the early 1900s.

I did a little research, and I discovered that all the big inventions which characterize the modern age came in around this period, 1900, 1901, 1902. The Wright Brothers were 1903 and I think the telephone was-this I'll mess up -1890, whatever. Automobiles first became really available' around 1903. The automobile in the story is a 1903 Oldsmobile which is a real model of a real car. I remember we had a discussion about-there are a lot of neat-looking old cars and there were neater ones from 1910-11, more picturesque, but we said, "No', let's go with the real one, even though it looks a little dumpy." So a person who was born in 1838 would find himself really in our world when he was old.

I have a

stepfather who's 72; he was born in 1907, I think. Well, you can

imagine-in 1907 the Wright Brothers had only had their flight four

years ago. There was no commercial air traffic-and now we're on the

moon. I'm sure the same thing will be true when you and I are old.

There would have been in Jonah Hex's time an incredible

transformation of the world, and so that became very exciting. And I

think you're right, that Jonah Hex was living a 19th Century life in

the 20th Century. But it was over-Hex was an anachronism. The thing

to find out was the best way for it to be over. It made me very

unhappy, that story. It made me very sad and upset. The people who

think that story is same sort of a sadistic toying with the reader

are really wrong because I got very choked up writing that story,

because it was the death of a character that I really loved-not only

loved, but I feel is really me.

I have a

stepfather who's 72; he was born in 1907, I think. Well, you can

imagine-in 1907 the Wright Brothers had only had their flight four

years ago. There was no commercial air traffic-and now we're on the

moon. I'm sure the same thing will be true when you and I are old.

There would have been in Jonah Hex's time an incredible

transformation of the world, and so that became very exciting. And I

think you're right, that Jonah Hex was living a 19th Century life in

the 20th Century. But it was over-Hex was an anachronism. The thing

to find out was the best way for it to be over. It made me very

unhappy, that story. It made me very sad and upset. The people who

think that story is same sort of a sadistic toying with the reader

are really wrong because I got very choked up writing that story,

because it was the death of a character that I really loved-not only

loved, but I feel is really me.

CATRON: Were you writing your own death?

FLEISHER: I hope not.

CATRON: That's only a half-joking question.

FLEISHER: Well. that's why I was upset. ,

CATRON: It was not a heroic death, and I think a lot of people might have wanted It to be a heroic death.

FLEISHER: Yes. they did. Well, you say a lot." I don't really know what the, response was. Most of the response about that story. let me say, was favorable. Look, if I'm wrong, I'm wrong. I don't read a lot of fan magazines. But my impression was that the story was favorably' received. The mail was certainly favorable. I think there were one or two negative letters out of 150, or a very large number. And letters continued to come in for a year and a half. I saw when I was at Marvel a few weeks ago, a British fan magazine, whose readers had selected "The Last Bounty Hunter" as the best story of the year, tied with Superman Vs. Muhammad All. So my impression is that reaction was favorable. But certainly there were people who felt angry-and that gets us back to something we were talking about before-they were angry. "How dare he write about a death that's not valiant? Jonah Hex could die, but at least he should die saving a whole city." I didn't think that's how a person like that would die.

CATRON: He got shot with both barrels from a shotgun, one after the other. .

FLEISHER: Right.

CATRON: That is a pointless way to go.

FLEISHER: Well, yes it is. You live by the sword, and you die by the sword.

CATRON: Hex certainly lived that way. Hex always had, not a casual, but a blocked-off view of life and death.

FLEISHER: Let me say something about this, and I don't mean to thwart you, but I should express my feeling about it. We used to sit in English class in college and we used to read and analyze these great books. And' we would dissect them, in what I thought was a very dry, unrewarding way, and we would rob them of all their richness and all their beauty. I don't think that it's really useful for us to analyze the inner motives, to analyze Jonah Hex in the story. The story wouldn't have needed to be written if it was as good to just cite these motives.

I

think what's happening in that story is 'that Jonah Hex is an old man

who is living the only life he ever knew, and it's a violent life, a

life of constant danger and death, and merely making a life for

yourself where you expose yourself to that much danger is an

indication of a certain amount of self-hatred, do you understand? If

you really cared for yourself, you'd do something that was safer.

I

think what's happening in that story is 'that Jonah Hex is an old man

who is living the only life he ever knew, and it's a violent life, a

life of constant danger and death, and merely making a life for

yourself where you expose yourself to that much danger is an

indication of a certain amount of self-hatred, do you understand? If

you really cared for yourself, you'd do something that was safer.

He's a tragic person. This is the only life he knows and his life has become outmoded. It's like the guys in The Wild Bunch. You have a person-the person being Jonah Hex-who's so shrewd and so cunning and so able, given the infirmities of old age, and then suddenly he does something stupid. It's like Wild Bll Hickock, who used to like to play poker, and never accepted the chair that would expose his back to the door of the saloon. And when Wild BW Hickock was murdered by a drunk named Jack McCall, it was the only occasion on which Wild Bill Hickock had ever accepted a seat with his back to the door. The only time. He came into a saloon, there was one seat vacant, he took the seat. a drunk came up behind him and blew him away. And if you have a psychological bent, you have to say,. "Why on this occasion did this person do something-a person who's at home in this violent milieu-why did he do that?" Well, part of him must have thought it was over, and he wanted to go. And I thought that, to me, it was right that that would happen. ,

CATRON: Okay, let me ask you about this. In a lot of your stories, violence-and death-comes upon people who are innocent, who are seemingly undeserving of anything like that. It's sort of like a gigantic roulette wheel, it just picks people off for no reason.

FLEISHER: Yeah. it comes from 'nowhere. Well, because I think that's what's really scary. I don't know if I can successfully delve into all the reasons for these things, but of course that's what's frightening. There's an EC story of which I'm very, very fond, about an average joe, who says goodbye to his wife and kids in the suburbs. He's going to the city to work, and all of a sudden he's dragged into an alley by a mad scientist who drags him into his laboratory and transplants his brain into the body of a gorilla. So now you have a big gorilla walking around with this suburbanite's brain. It's very horrible, and it's horrible for the same reasons that you're talking about. I think that's what's scary-what's scary is the average schmo who walks out of his house and a sniper shoots him for no reason.

CATRON: Does that concern you, living in New York?

FLEISHER: Yeah. Yeah. .

CATRON: It's not exactly a reassuring way to write about it.'

FLEISHER: Well, it's not meant to be reassuring. It's meant to be disturbing and unsettling. I've noticed another thing about the fans, if I may say this, that there is a ragefor order. For example, in my mystery story "Cake," two people perpetrate a crime. A ma n and a woman commit a crime, and he's really the villain. She doesn't really want to go along with it, but she's his girlfriend and he drags her into it. So she's involved in something bad, in a...

...CATRON: You've written two female characters: The Black Orchid and Spider-Woman. And yet, you also write Jonah Hex, who is a very macho character...

FLEISHER: Really?

CATRON: Yeah. I think so.

FLEISHER: Huh. Okay.

CATRON: Although I've noticed he has been mellowing in recent issues.

FLEISHER: Well. I've been

mellowing in recent issues. I think you're better equipped than I am

to draw conclusions about Jonah Hex. You've made a number of very

astute observations about the series. I think Jonah Hex has probably

cried, for example, more than any hero in comics: Jonah Hex has

probably shown more real tenderness and grief than any character I'm

familiar with. Now look. I'm not saying that Jonah Hex is a pussycat.

I'm just saying that I think it would be a mistake to overlook the

more sensitive aspects of Jonah Hex that frequently appear in the

stories.

FLEISHER: Well. I've been

mellowing in recent issues. I think you're better equipped than I am

to draw conclusions about Jonah Hex. You've made a number of very

astute observations about the series. I think Jonah Hex has probably

cried, for example, more than any hero in comics: Jonah Hex has

probably shown more real tenderness and grief than any character I'm

familiar with. Now look. I'm not saying that Jonah Hex is a pussycat.

I'm just saying that I think it would be a mistake to overlook the

more sensitive aspects of Jonah Hex that frequently appear in the

stories.

CATRON: No. it's certainly not out of character for Jonah to cry.

FLEISHER: See. I think of something like Shaft as macho. If Jonah Hex is macho, okay, I'll accept it, but I don't think of it that way. Jonah Hex certainly is chauvinistic. if that's what you mean. I did a story about woman's sufferage, in which Jonah Hex thinks it's ridiculous that women should vote.

CATRON: That was a great story-and he ends up wearing the armband in the end.

FLEISHER: Right.

CATRON: That was cute. Nice touch. I want to deal with heroines and women in your stories-how difficult is it for...

[FLEISHER]...There's a lot of antagonism between the sexes. There's a lot of antagonism between the races. I am not free of those feelings. I try in my life to behave as well as I can. In my stories I give free expression to my feelings. It may be that those feelings are disturbing to people who probably have those feelings too, and they don't want to have to face them. But let's give them the benefit of the doubt and say that they want to see for example, in some people's stories-this is getting into a touchy area, but who cares?-in some people's stories, whenever you see a Black person, they're always a scientific genius or something. It always makes me feel a little uncomfortable.

I mean, I'm sure there are Black scientific geniuses, but in Jonah Hex, there's a Black who's a servant, and I don't really care if Blacks would rather see themselves in comics as scientific geniuses. I'm writing about a world 10 years after the Civil War and I'm trying to be as honest as I can about it. So it's inevitable that my feelings about women-not all of which are noble infect my stories. But that's the place for those feelings

Can I give you an example that I can focus on clearly? I'm trying to learn to write super-heroes better-trying...

[FLEISHER]...As a

writer, I'm most gifted at verbal things and at characterizations.

Frequently the artists are much more interested in the action than I

am, and it's hard to win enough characterization space, whereas if I

write the script, I put the characterizations right in there.

[FLEISHER]...As a

writer, I'm most gifted at verbal things and at characterizations.

Frequently the artists are much more interested in the action than I

am, and it's hard to win enough characterization space, whereas if I

write the script, I put the characterizations right in there.

I'm going to tell you something that may surprise you. When I write a Jonah Hex, and I go over the allotted number of pages, the first thing that comes out is the action. Because to me the important thing in a Jonah Hex comic is Jonah Hex and how he feels and how the various characters interact with one another and-I don't need the gunfights. It's nice to have lots of room. That's why 1 liked the Jonah Hex Spectacular. I love doing those long stories, but the important thing to me is the characterizations, and if you really look at Jonah Hex-well, in Jonah Hex, of course they fire guns, instead of throwing punches at each other, but there's very frequently less action in a Jonah Hex story than in a regular super-hero story. It may be action of a more lethal kind, I'll grant. you that, but there are very frequently stories with several pages strung together or people talking. There's an issue of Ghost Rider, which I would like to advertise, #46, in which Johnny Blaze is involved in a motorcycle competition with another great stunt cyclist, and Johnny Blaze is scared that he might lose. It's late at night and he's, in a little garage with his bike. There's a single light bulb shining overhead. And he's in that garage for two pages pacing the floor and worrying about what's going to happen tomorrow, and I know that Don Perlin will do a bang-up magnificent job on those two pages, and it's a pleasure to be able to do something like that with an artist who you know will make it exciting and meaningful. It's' just silly to say you can't have' two pages in a comic book of a character soliloquizing.

[1] A news item in the same issue of The Comics Journal mentioned that it was reported in the British fanzine Bem that the new character's name was tentatively to be Dakota, and that he would appear in Jonah Hex (#42-44) before being spun off into his own book. Those three issues were to be drawn by french artist Gerald Forton (which they were) and Fleisher was going to write the series when it began (which it didn't).

Michael Fleisher Links

- Interview 2008

- What ever happened to Michael Fleisher?

- What ever happened to Michael Fleisher? Part Two.

- Work listed in The Grand Comics Database

- The Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes: Volume 1: Batman (1976) review

- Wrath of the Spectre Review

- The Insanity Offence The Fleisher/Ellison/Comics Journal Libel Case , Charles Platt

- TGSB author and more

- Work for 2000AD

- An interesting footnote to the Fleisher/Ellison/Comics Journal Libel Case; in 2006 Fantagraphics seralized on their website their book Comics as Art: We Told You So which chronicles their publishing history. In it they made some comments about Ellison's behaviour at the time of the case. Ellison took offense at these comments, and sued them, but after some mediation the two sides have come to an agreement which should be the end of he matter... perhaps. The only good thing about their war of words is that a few folks were spurred to look back at Fleisher's work, such as Comics Should be Good