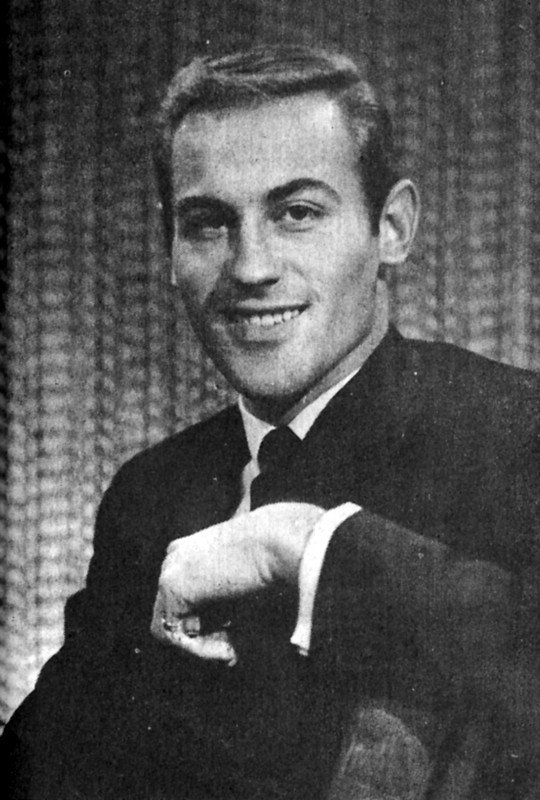

From the New Zealand TV Weekly. 22 April 1968

Born: In Australia, in 1940.

Height: 6ft 1in.

Hair: Blonde.

Eyes: Brown.

Married: No.

Hobbies: The “outdoor” life, sun and surf.

PETER SINCLAIR came to New Zealand with his parents as a small child, and became a pupil of Christ’s College in Christchurch. He continued his education at the University of Canterbury, where he took an arts course.

It was during a return visit to Sydney that Peter decided upon his future career, when his first job, as a radio announcer, brought him in contact with a number of show- business personalities. '

Still undecided, he returned to New Zealand and a further year of university studies, but this came to an abrupt end when he took a job as an announcer at 3YA Christchurch. A year later he returned to Sydney for a two-week holiday, which turned out to be 2 1/2 years’ work.

When he returned to New Zealand he had made up his mind-no more broadcasting, and for a while he earned his living compering. fashion parades. It was inevitable, however, that he should return to his first love, and after spending some time as a radio announcer, he made his Television debut in Let's Go.

This was followed by a year-long world tour, much of which was spent in Greece.

Now a free-lance compere, Peter lives in Auckland where he still conducts the New Zealand Hit Parade and The Late Show,

The Unlikely Schoolboy Who Became Your Compere

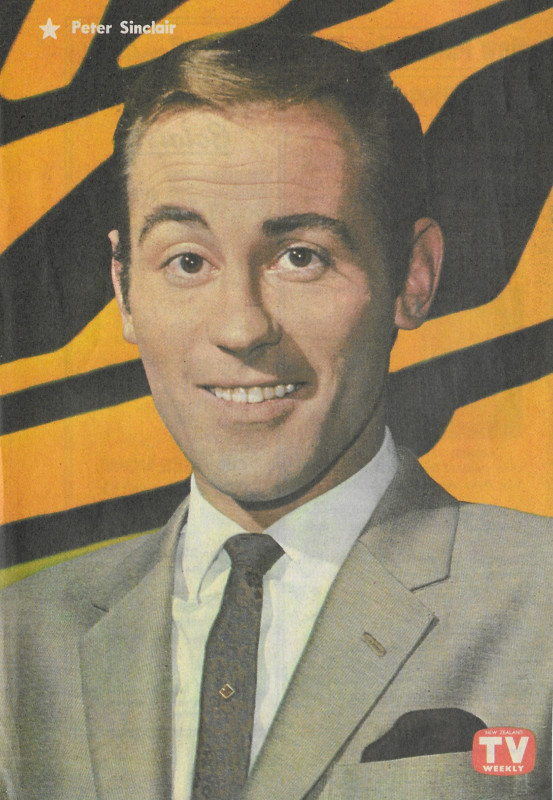

From the New Zealand TV Weekly. 23 January 1967

Peter Sinclair was born in Sydney, educated in New Zealand. Always intended to be a journalist but a brief stint writing about the laying of foundation stones and events of similar breathless interest

made him decide otherwise. Enrolled at Canterbury University and then returned to Australia. On one of his several trips back to New Zealand he became an announcer on 3YA and has remained an announcer ever since.

Howls of laughter would probably have swept across the lower fourth if anyone had suggested, when I was at school, that I might eventually become a compere of pop shows on "Television"-then only just in the process of becoming a word in the New Zealand vocabulary. And even I--studious and untalkative, bespectacled librarian, indifferent debater-would have joined in the amusement at such an unlikely idea. I offer this as encouragement to any would-be compere. If I could become one, almost anybody can.

Writing to me, the editor of TV Weekly asked: Why have you succeeded when so many others, eager and enthusiastic, have failed?

I think there are two main reasons.

The first is the period I spent in radio before being asked to tackle TV. Eagerness and enthusiasm are no substitutes for experience. Radio itself is a hard medium to master, television even harder, and the newcomer has learned no tricks of these difficult trades.

In TV work, as well as the problem of what to say, there are the additional problems of how to say it and what to do when you are saying it. These problems have to be solved simultaneously, moment by moment, as the show rolls; if one element is missing, the other two alone can't save the compere, and his performance fails.

We've all seen comperes who forget their scripted patter, or whose nervousness won't let them put it across effectively, or who stand rigid as quick-frozen runner beans, eyes glazed and sweat bursting through the make-up, their whole performance and possibly the whole show ruined by the urgency of their desire to remember what they are saying.

For a man who earns his living by the tongue, two problems are eliminated-the what and the how. There is no need for him to grope for words; they are at the tip of his tongue. His delivery of them, his inflexions and pauses, are automatic things, conditioned by long sessions behind a microphone. He can concentrate on the cameras and on the flow of the show itself, on where he should be and what he should be doing at any given moment.

Radio work, I think, is the best way to get this assurance. Experience in the theatre is not quite the same and, from the point of view of TV, not quite as good. An actor certainly scores in poise and presence, but he is used to memorising and then disgorging the words of others. Personally. I feel that the secret of really good TV work is the ad lib-unscripted continuity delivered by someone who knows his subject backwards, is entirely at ease, and whose total personality is carried into the lenses with every word he speaks.

It is easy to see that this is the case by looking at the most successful of own local productions, past and present. Graham Kerr is probably the most dramatic example of TV naturalism. His is the flair of the gifted amateur, rising far above mere professionalism. For 30 minutes he navigates his sprightly way through the shoals and hazards of a live TV show with no script to guide him, any slips becoming a part (often the best part) of his performance.

The same applies to the various editions of Town and Around. The best hosts, I know, rely only in part on scripted material. Our finest commentators use only jolted notes-they flash out their commentary on camera with ad lib. I'm sure it will be a long time before they forget the work of commentators from various American networks during the visit of President Johnson to this country-how these men stood before the cameras without notes of any kind and for five minutes or so delivered a faultless description of the President's progress and a closely reasoned analysis of the significance of his Pacific tour. Our own coverage of the Manila conference suffered very badly by comparison.

And on the pop scene, Let's Go was a completely unscripted show, apart from the opening, the closing, and various key phrases - called "cues"--which warned the producer to alert the telecine operator, the floor manager, or the sound technician that the show was about to move on into another sequence.

Successful ad libbing is a skill which takes a long time to acquire, and only radio broadcasters (with the possible exception of politicians) are in a position to acquire it. It means saying the right thing in the right way while being at the same time conscious of various other factors, the most important of which is time.

Time has a habit, in radio or TV, of expanding and contracting in a bewildering and unpredictable way. One of the hardest things for a novice to learn is how to balance his material with the time available for it--how to avoid a too leisurely opening followed by the frantic mutilation of his material for a high-speed close. In television the time factor is critical. A radio broadcast can sometimes run over; a TV show must not. There is nothing like TV compering for an appreciation of the second as a unit of time, of how much can actually be said in five of them, so that 30 seconds can become an abyss of time it is almost difficult to fill. Only experience can teach a compere how to say something in 15 seconds, no more, no less, for some split-second effect of timing. The opening continuity of the recent pilot show for C'mon, for instance, was very tight, lasting exactly 20 seconds, and had to coincide precisely with the raising of the studio lights and the band breaking back into the second chorus of the theme. I blew it at every rehearsal and only got it right once-- on the actual take!

The second reason is that in radio I've learned to be a salesman - a salesman of the sound, of the show and of myself. In no field is lack of enthusiasm, a "phoney" approach, more evident than in pop music. You can't fool teenagers. When I compere a show I am selling all the time-selling the band, the artists, the total sound. I am involved with every- thing that is going on. When the guitars begin to twang, like an old warhorse hearing the battle-trumpets I can feel a response inside myself, a growing buoyancy and vitality. So that when the show is finally in motion, I have become part of it and have started to enjoy myself. Genuine enthusiasm is contagious. If you are "sold" yourself, it isn't hard to sell other people.

I've been lucky, because generally I've had the right producer and the right show at the right time. In the same way that a poor compere can undermine a show, an uncreative producer can destroy it. You can think of two or three TV disasters in this country, and I think they can all be attributed to the producer, whose role in the success of any show is rather more vital than the compere's. Ideally, the two should work together, the producer supplying the visual bounce and the compere acting as a shot in the arm throughout the show whenever the action starts to flag.

But the most important decision is the producer's. What kind of show is it to be? In the past the net has often been cast too wide. The NZBC, in a natural desire to get as much value for its money as it can, has favoured an elusive abstraction called "the Family Show." Theoretically, every member of the family, from grandma to 10-year-old grandson, is supposed to enjoy some parts of this show, so that although no single individual is expected to like the whole thing, the Family, as an entity, can be deemed to have been satisfied. In practice, of course, nobody is satisfied. The gulfs between the three generations is far too wide. No, I believe the secret of TV success lies in a narrower focus - a conscious attempt to please in a total way one clearly defined segment of the TV audience. In my own case, this is the teenager. My performance is designed for those who are about 11 to those who are about 20; if in fact I please the average 15-year-old girl I consider I have done my job. If anyone outside the age-limits enjoys the kind of show I do-fine! If not-tough! The show was not intended for them.

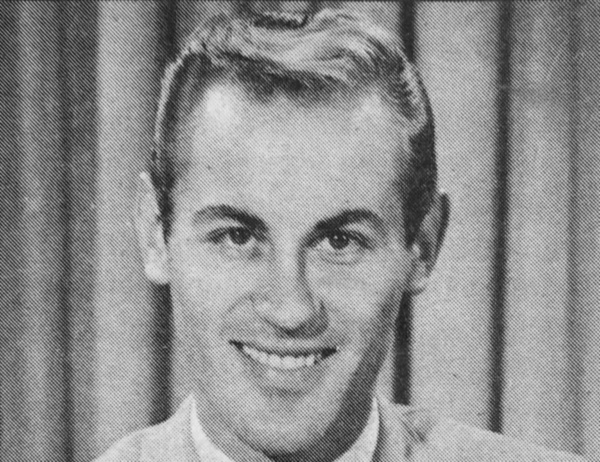

Peter Sinclair, compere, introduces hillbilly singer from Otago Central John Hore for the NZBC programme Countdown 64.

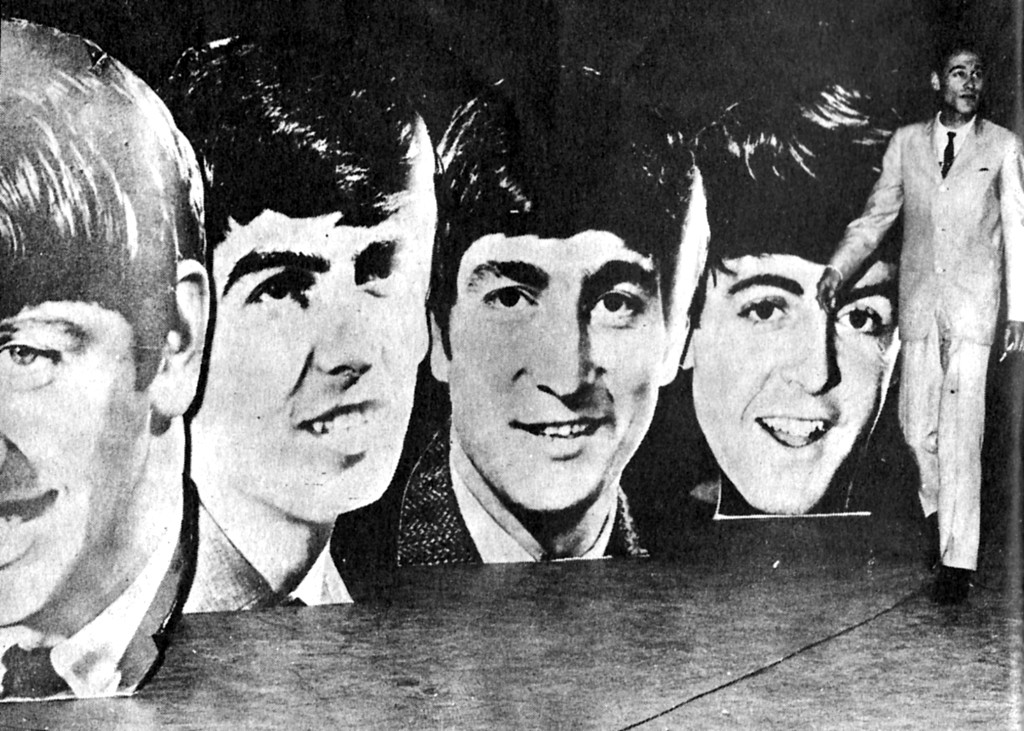

For the show Countdown 64, Peter Sinclair thoughtfully walks towards the cameras, past giant photographic blow-ups of The Beatles.

Comments powered by CComment