Dramatisation of Chief Titokowaru's attack on Colonial forces at the Turuturu Mokai redoubt in July 1868, focusing on two army deserters who joined Titokowaru's forces.

Dramatisation of Chief Titokowaru's attack on Colonial forces at the Turuturu Mokai redoubt in July 1868, focusing on two army deserters who joined Titokowaru's forces.

Credits

Charles Kane: Alan Jervis

Titokowaru: Napi Waaka

Kimble Bent: Peter Vere-Jones

Lt Col T Mc Donnell: Anthony Groser

Major Hunter: Ray Henwood

Extras Include: John Banas

Producer: Chris Thomson

Writer: Warren Dibble

Designer: Cedric Leeming

Editor: Michael Horton

Photography: Waynne Williams

Lighting : Iain Hill

Screened Monday May 3rd on Northern TV and then later that month on to the other channels.

http://filmarchive.org.nz

During the land wars of last century the Hauhau chief Titokowaru developed a successful guerilla campaign in south Taranaki. The Killing of Kane is based on his attack on the Turaturamokai redoubt at Hawera on July 16, 1868, when Captain Ross and half the garrison of 20 were killed. The cast and crew worked at Hawera, where bulldozers were used to recreate the redoubt only 50 yards from the original site. Titokowaru is played by Naapi Waaka, and Taranaki Maoris appear as members of his tribe.

The Killing of Kane was shot on film, in colour-the biggest "on location" TV drama production attempted at that time in New Zealand. Producer Chris Thomson sees the use of colour as further valuable experience for local producers. Location filming itself is an education: We found that if the weather's fine you keep on going till you drop.

The Listener, 1970

Death to the Pakeha

From the NZ Listener. May 3, 1971

By Alexander Fry

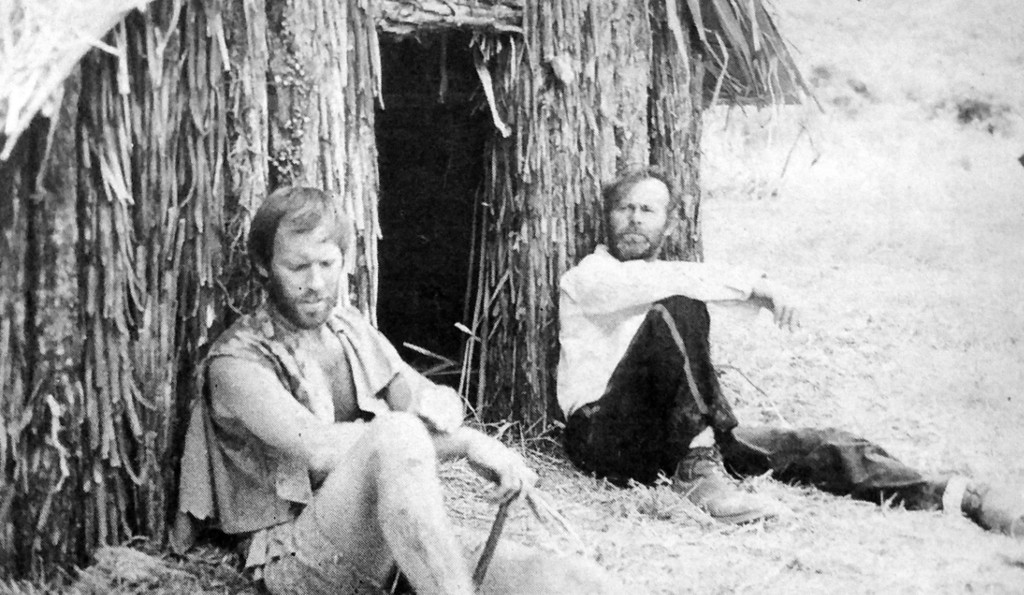

Alan Jervis (Kane) and Peter Vere-Jones (Bent).

Refighting the Maori Wars for televison can be almost as hazardous as fighting them in the first place. One man suffered powder burns when his old musket backfired in The Killing of Kane a drama-documentary of the Taranaki War. Another had to feign triumphant delight as he carried from the battlefield a bleeding “human” head.

The NZBC, diplomacy had to be skilful too, or its Pakeha filmmakers might have suffered another bloody comcuppance at the Turuturu-Mokai redoubt. Taranaki’s Maoris have long memories, and the European land-grab of the 1860s is not forgotten.

Old people were not keen to take part in the film

, says Chris Thomson, the producer. But we did get a couple of old women with moko who were prepared to sit around in some of the crowd scenes. They came and watched us first, and checked over the kainga we were building, and satisfied themselves that we were doing all right.

Warren Dibble’s script for The Killing of Kane must have helped reconcile Maoris to enacting a Land-War incident. At Turuturu- Mokai a war party of 60 men carefully selected for the job by Titokowaru, the Ngati Ruahine chief, attacked an Armed Constabulary redoubt, killing 10 and wounding six of its 25 defenders, for the loss of three men.

It was one of a series of victories scored by Titokowaru, a master strategist and tactician, in 1867 and 1868, before he lost his mana as an invincible war priest and war captain because of an illicit liaison with another chief’s wife. After that he faded into obscurity.

In contrast to the able and imperious Titokowaru, the pakeha “heroes” of Dibble’s play are Kimble Bent and Charles Kane (sometimes called Charles King), two British deserters who lived virtually as slaves under Titokowaru’s protection. Bent deserted the 57th Foot Regiment and Kane the 18th Royal Irish Regiment, the former after 25 lashes at the triangles for a disciplinary offence, Kane after 40 lashes.

The Killing of Kane is not strictly a play or a documentary, says Chris Thomson, but a little of both. It’s as historically accurate as humanly possible, and all the characters except the very minor ones were real persons. During the filming we kept running into descendants of all the characters. Much of the dialogue is invented of course.

The first seven or eight minutes of the film are almost pure documentary, and then gradually it becomes the story of the two deserters. The whole thing adds up to a play about loyalty and corruption. The deserters are men of divided loyalties, corrupted by their attempts to ingratiate themselves with Titokowaru. The Maori leader is corrupted by the Hau Hau mixture of Christianity and paganism, which led him to revive such primitive (and dying) practices as cannibalism.

Chris Thomson and his crew spent a long time trying to find Maoris of the correct lineage who were also prepared to take part in the production. We stuck reason- ably to the tribes

, he says, but just by chance Titokowaru is not Ngati Ruahine but Arawa. The part is played by Napi Waaka, a Methodist minister in Hawera who had some experience in show business and who is also keen on bringing Maoris into productions like this and making them aware of their Maoritanga.

Professional actors fill the three Pakeha roles — Alan Jervis as Kane, Peter Vere-Jones as Bent and Anthony Groser as Colonel McDonnell, the military commander in the area. Irish or Irish-derived accents are called for, because both Kane and McDonnell were Irishmen and Bent was American born.

To make The Killing Of Kane, the NZBC crew had to rebuild three sides of the Turuturu-Mokai redoubt, as well as Titokowaru’s fortified village at Te Negutu o te Manu — and they kept running into problems. Taranaki is full of telephone poles,

says Chris Thomson. They’re all over the place. So we had to build the redoubt on the brow of the hill nearby rather than where it actually was.

Ironically, that is where the redoubt should have been in the first place. The heavy Pakeha casualties at Turuturu-Mokai were caused partly by the fact that the redoubt could be fired into from the hill, and Titokowaru’s men did just that.

George Tuffin, an old Armed Constabulary man, told James Cowan in 1918 what it was like: I received four wounds as I lay in the north-west angle of the redoubt. I was shot in the Ieft arm, through the back near the spine, in the right hip, and in the right ankle. When I got to the angle there were five men there. Of these, three were killed outright, including Sergeant McFayden, and one of the Beamish brothers was mortally wounded.

Although his casting and set-building problems were big enough, Chris Thomson asserts that they were not the main ones.

Our two big problems were logistics and filming in colour,

he says. We had a crew of about 25 and a cast of many more. Any Maori who turned up would be wrapped in a blanket and shoved into the film. Not all of them would turn up next day, so our continuity is a little strange at times. We had to provide meals and toilets in all kinds of places for these people and organise bus and taxi fares. One needs great administrative talent.

As for colour, it’s very much more difficult to shoot and much more restrictive than black-and-white. It also takes much longer.

(The Killing Of Kane cannot yet be shown in colour in New Zealand, but it was filmed in colour at the request of the NZBC’s Overseas Programme Service for possible sale abroad.)

To ensure verisimilitude, designer Cedri Leeming worked from photographs and plans made in the 1860s and from sketches by people in the Hawera district who knew something of the places and events in the film. And great pains were taken with costumes and weapons — except for extras who scarcely appeared on camera.

We managed to get muskets — the one thing we're pretty certain are authentic,

says Chris Thomson. To fire them we had to use percussion caps and rolls of lavatory paper filled with gun powder. That made the correct sheet of flame and the right noise. Most of the cast were terrified of them. We had to throw out one sequence where the war-party came charging out of the bush — holding their muskets up in the air and well away from their bodies!

A few of the Maoris used their own taiahas — they wouldn't use anything else — but those in the background just got correctly shaped lumps of wood. For close-up work, Napi had proper taiahas and meres, and a proper cloak to wear.

Once the Maoris accepted that we were were making a genuine film they had a ball — they loved it, and were marvellous. They turned up first thing in the morning In their cars with their picnics. The women would weave fiax blankets to scatter round the place and headbands for the cast to wear. And on the last night they made a huge feast.

There is a story to that. We bought two pigs which on wandering around the village, and then for one scene we had to have a human heart. Kane took part in the battle at Turutura-Moka and to get in favour with Titokowanu he brought the heart back to the pa but it didn’t work, as it happened, because the heart was supposed to be left the battlefield. But to get that heart for the film we had to kill one of our pigs. The result was | farewell feast.

The facts of the real incident related by James Cowan bear the story of the heart — or rather hearts — though Kane’s role in the matter is not mentioned:

Then, in the midst of fighting, the pagan ceremony of ti-whangai-hau, the offering of the foeman’s heart to the gods of battle was performed by one of Hau Haus, the young Tihirua. The heart of the first man slain (Lennon) was cut from, body even before it had ceased to beat. It was the ancient custome to offer the heart of the first victim to Tu and Ueamika, the deities of war. Lighting a match, Tibirua held it under the beating heat until the flesh was singed and began to smoke.

Then, crying out 'Kei au a ??' he threw down the heart, and snatching up a tomahawk, and rushed into the fight. When Captain Ross was killed, his heart too, was cut out. a human heart, either that of Lennon or Captain Ross, was found on the ground outside the fort after the fight. The other was probably Carried off at Te Ngutu-o-te-manu as the mawe ... the battle, a trophy of oblation to the gods. This savage rite, revived by Titokowaru, was warried out at several occasions in the war of 1868 -69.

In New Zealand history, perhaps only the wars of last century provide such inherently dramatic material, and TV seems certain to draw heavily upon them time goes on. Even now The Killing of Kane is not isolated. The week it is screened viewers can see a Survey documentary, War in the North, which chronicles the rebellion of Hone Heke leading up the the Battle of Ruapekapeka.

The documentary interest of this period lies in the battles themselves, in which the Maoris’ remarkable flexibility and military skill gave them most of the victories, Titokowaru himself perfected methods of fortification which made his positions all but impregnable to European artillery.

The dramatic interest in the interaction of widely differing cultures and outlooks, leading up to the one great clash and continuing to this day. Chris Thomson draws no conclusions from his experience in filming The Killing of Kane, but there is material for another film in the spectacle of his Maori and pakeha cast re-enacting a bitter incident in an unjust war, then feasting together — before going happily off in their several directions to see how they will look on TV.

Comments powered by CComment