Current Affairs.

Behind the scenes:

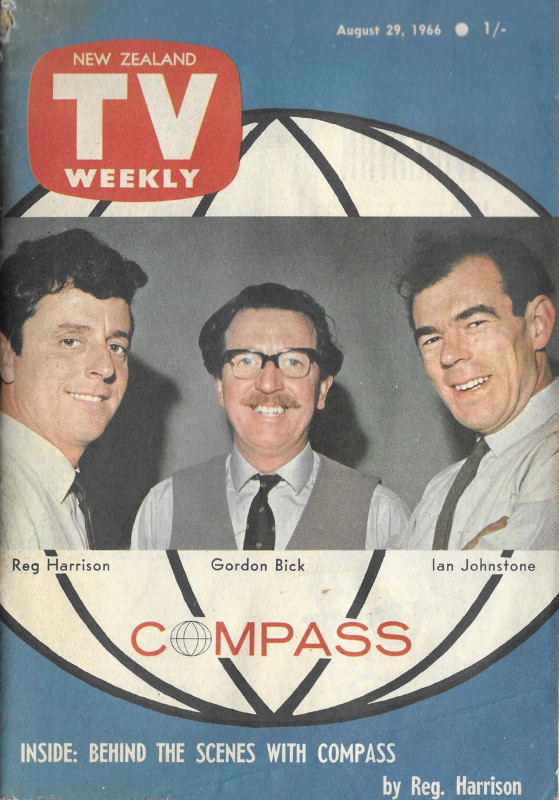

First published in New Zealand TV Weekly August 29, 1966

First published in New Zealand TV Weekly August 29, 1966

Dr Reg. Harrison, Department of Political Science, Victoria University, Wellington, has made many guest appearances on Compass programmes. Here he appraises WNTV1’s outstanding documentary series, its staff and the timidity of certain NZBC administrators.

Provocative and opinionated, it's the prestige NZBC television programme.

ls Compass a success? If it is, the newspaper critics and the letter-writers explain why on the days when they don’t like the programme. It is provocative and opinionated. It is biased to the Left and it is biased to the Right. It has been called militaristic. And it has, one parochially-minded reporter pointed out, a lot of Pongos around on the staff.

The only really important thing to add to this is the fact that it is a programme designed for a New Zealand audience. There you have the basic formula: hit the viewer hard, knock him down, and keep on hitting him while he’s down. And always remember he’s a New Zealander, not an American or a Frenchman or an Englishman.

This last stipulation is very important because, to viewers in the bigger, richer countries, television is constantly holding up a mirror, not just in documentaries and magazine programmes, but in the avowed entertainments like Coronation Street and Peyton Place. They can see themselves as others see them. Rabie Burns’ fervent prayer has at last been answered. A much smaller proportion of programmes here shows New Zealand to the New Zealanders, or tries to formulate a distinctly New Zealand attitude to events abroad. When Compass producer Gordon Bick talks over with his team possible topics for the programme, this special New Zealand need is the deciding factor.

Topics

The topics that are discussed are suggested by a wide variety of people. Publicity seekers, fools and persistent bores ring up, but so do obviously informed, intelligent members of the public with really good ideas. Issues in the headlines are sometimes the obvious choice, but what is momentarily topical doesn’t always make the best Compass material. There would be no point, for example, in climbing on to a very broad wave of public opinion and riding with it to the safe shore. On the other hand, if the wave runs up against a cross-current this is a compelling reason for Compass to get into the troubled water.

Heated issues

This is why issues which excite some heat in the House of Representatives, including perennials like the Bud-get and import schedules, are likely to attract Compass attention; so are public statements by well-known people which seem to have upset the newspapers and the general public.

Some very broad categories are intrinsically interesting because of the huge body of folk-lore and myth that has gathered round them. See, religion, liquor and drugs, and money, spring to mind immediately. Are mothers of illegitimate children loose women or victims of circumstance and ubiquitous human weakness? Are homosexuals criminal, sick, or neither? Should the church stick to spiritual guidance? Is a man in a pub neglecting his wife and children? Are Maoris more prone to drunkenness than pakehas? Is marijuana or opium worse than alcohol? Can we afford to invest in industrial development, more defence, immigration? Is the money being spent efficiently?

Sample opinions

Those are some of the questions, within the broad categories, on which we may reasonably suspect there is a majority view-a folk myth. They are also questions which are so complex, once you look at them closely, that, like as not, the majority is wrong. First job then for Compass is to go out and sample opinion, get a rough idea of what the majority believes and then examine that belief. Show it up by research, in the light of the facts. Get the expert view. Hear out the minority critics.

And if most people are irritated and annoyed with the result, so much the better. The programme has been justified.

Interference

Final decision on topics, however, is not vested firmly enough in my opinion with the producer. There is too much “interest ” in the programme from the higher-ups in the Public Affairs section, some of whom, I suspect, suffer badly from that nasty ailment “cold feet.” These are the people who worry about what ought and what ought not to be dealt with in an election year-precisely the time when every political issue ought to be wide open to politically unprejudiced investigation. I sometimes feel that the desire not to abuse the more independent “Corporation” status occasionally makes the NZBC more timid than the old NZBS in dealing with public affairs. In any case it is quite wrong to make a talented, creative production team operate in the wishy-washy world of collective caution which is characteristic of government by committee. And the Compass team is talented. I regard it as a privilege and a pleasure to work with them.

Compass team

Though they are a team and, in a way, it’s wrong to single anyone out, the key people are undoubtedly Gordon Bick, Ian Johnstone, Julia Mason and, since November 1965. Bob Higson.

Gordon Bick has produced the programme since Alan Martin was absorbed into the higher paid bureaucracy (a necessary waste of a good producer!) Gordon is English. He has an authentic, ex-R.A.F. handlebar moustache, casual sartorial elegance, and the filthiest, most unshapely hat in the whole of New Zealand. He puts the indispensable bite into the production, a searching iconoclastic attitude that he brings straight from Fleet Street. There is a refreshing brashness about him which springs from a very apparent conviction that news, and the critical appraisal of news is not a privilege in a democratic society but a right. Provided the reporting is accurate and the criticism fair, then no matter how controversial the news, it should be on Compass. In fact, if it isn’t controversial, it should not be on Compass. Amen to that.

lan Johnstone

Most viewers will be more familiar with Ian Johnstone-“front-man" extraordinary. Ian is a Scot, and a former school teacher. He has the same pleasant eloquence off the screen as on it. I would rate Ian higher than most of the B.B.C. reporter-commentators. Just compare his little masterpiece on Rotorua (or even his report on the fundamentally less interesting subject of the Chathams) with Alan Whicker’s feeble effort on the Barbados whites! Remember, When you see Ian Johnstone or Bob Higson reporting for Compass that they also do the production direction in the field, play a large part in editing the film once it has been processed, and help to write the commentary over the film. They really have to be all-rounders. Ian Johnstone’s scripts, incidentally, are worth careful attention. He turns an elegant phrase.

Bob Higson

Bob Higson did, among other things, the reporting on the very searching Mantapouri investigation, and the item on Wellington’s poor and needy which excited so much controversy. Bright and assertive, he’s also an Englishman with a journalistic background.

Julia Mason

Julia Mason is in charge of research. Julia is also involved in most other aspects of Compass work, and she finds time to do research for other programmes. If she ever left NZBC at least three people would be needed to replace her. She is a New Zealander, daughter of Helen Mason, the potter. Before coming to Compass, she taught biology at an Agricultural Institute in Tanganyika and she brings rigorous standards to her work. Research is quite properly regarded as an element of fundamental importance to the programme. The first step in dealing with any topic, therefore, is to pass it over to Julia. She hares off to the libraries, and telephones or goes to the offices and homes of businessmen, civil servants, Trade Unionists, Ministers, and so on, ferreting out information and cross- checking it. In a remarkably short time there will be four or five pages of accurate, concise, typescript on Gordon Bick’s desk, on anything from Abduction to Zoroastrianism. More research and enquiry is often needed during filming on location.

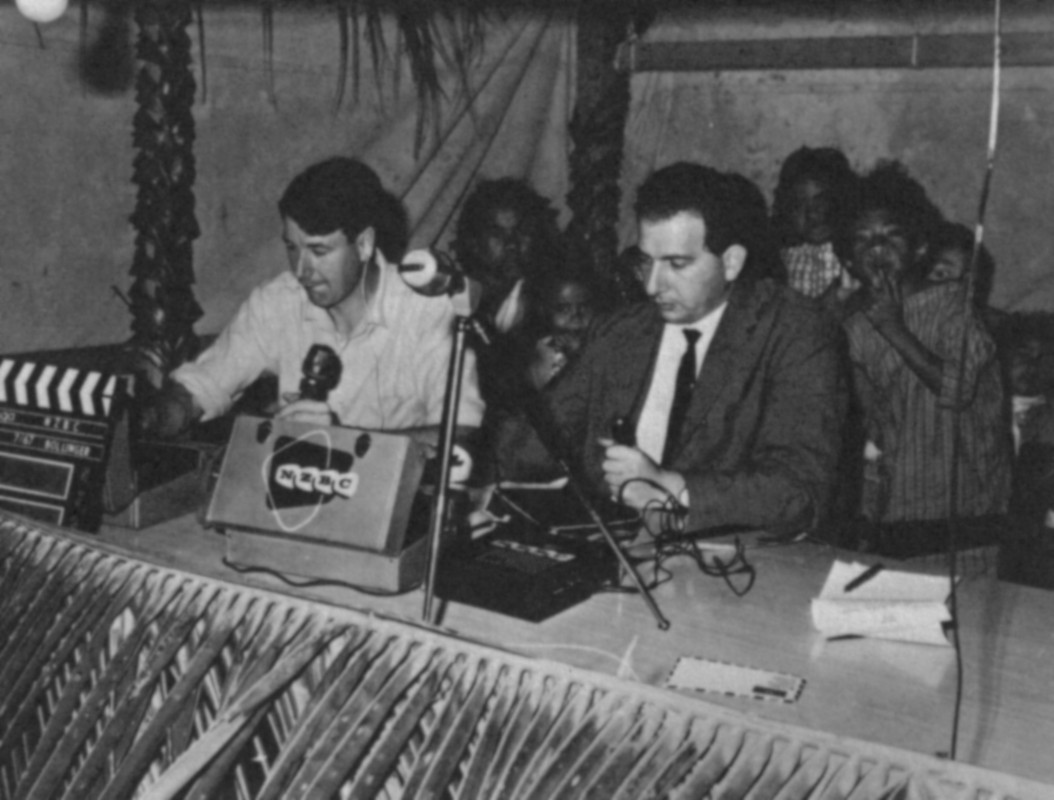

Bick organises

With the facts before him, Gordon can now decide what film is needed. A certain amount may be available in archives but on specifically New Zealand subjects more filming is usually necessary. A camera crew must be obtained. Most of the filming is now done by NZBC crews, but Compass doesn’t have a camera crew for its own exclusive use as do comparable programmes produced overseas, such as World Tonight and the Australian programme Four Corners. A crew and equipment may have to be hired from the National Film unit, and very occasionally a commercial film unit is used. A crew having been found, one of the production team is now assigned to the job. Filming has taken Compass people over the whole of New Zealand and the seas around. They have been to the Cook Islands, Fiji, the Tokelaus, and to Vietnam and Australia. Heavy and expensive cameras and equipment are dragged up cliffs, lowered down embankments, and shouldered across rivers. I’ve had to walk down the centre line towards a camera set up in the middle of Queen street, Auckland, in dense traffic. I’ve seen one cameraman push himself with his feet, lying on his back, camera whirring, through a crowd of dancing teenagers. The keynote is imaginative improvisation. You’ll be surprised, for example, what a good tracking unit Julia Mason’s little Fiat makes, with the roof open and the cameraman standing on the seat.

Interviews

Interviewing is an interesting business with techniques all its own. In the field, wind and background noises are very hard to contend with, ruining quite a few good interviews. There is a wind-proofed mike, covered with a plastic foam, but it’s not always available. As far as I know there’s only one in Wellington! The main thing is to get your subject relaxed but alert; I find it helps to ask males for their views on women, and vice versa, before starting. This is, incidentally, often a lot more interesting than the final interview.

Microphone shy

One problem that we do have to contend with is the reluctance on the part of many people to state their views publicly. They urge the interviewer to go and ask their next door neighbour.

I’d like to say what I think but my boss, my wife, my business clients, my constituents would object.You’d be particularly surprised how shy those devil-may-care, swashbuckling heroes, the wharfies, can be when you try to get them to talk on camera.People put on their best performance, we have found, in their own homes or offices rather than in the artificial atmosphere of the studio. This often means that cameras, lighting and sound equipment have to be lugged up flights of steps but it is worth it.

Editing film

Many hours’ work and several thousand feet of film may go into a topic that eventually runs on your screens for about fifteen minutes. An interview or run of film will rarely, if ever, be used as it stands. Interviews are out up and intermixed so that one complements another. A housewife expresses a complaint. You immediately see the mayor and then the vicar commenting on the complaint. The complaint of course has been “fed” to them by the interviewer, but he and his questions are cut out. Other film is subject to the same treatment.

The film finally selected for the complete programme must be scripted in sections and the commentary recorded. Then, on the day before the programme goes on, the whole film interspersed where necessary by studio introduction and linking commentary to camera, goes on to videotape. This is a matter of exact timing under studio director, John Terris. Given a successful studio run, the programme is now ready for the screen unless, as once happened, someone in Public Affairs exercises a veto.

In conclusion, let me acknowledge that Compass is a privileged programme within the Corporation. The budget is adequate, at least for operations within New Zealand, and the team, all things considered, enjoys a good deal of independence. The greatest privilege though is the one extended by the New Zealand public in watching and, apparently, liking the programme. This really isn’t to be taken as a piece of jolly, terminal soft-soap, because the public is watching a critical programme, a programme that tries, though it doesn’t always succeed, to get under the skin, to irritate, even affront people. The Ponges on the team are a deliberate, built-in menace, in this respect because they look at New Zealand with a slightly alien, enquiring eye. Incidentally, for similar reasons there are complaints in England that the BBC has been taken over by Australians and New Zealanders!

-by Dr Reg. Harrison

Later in 1966 Gordon Bick resigned because he was certain that only government pressure, indirectly applied, prevented the televising of a Compass programme on the conversion to decimal currency. He write a book about this and his views on television and broadcasting in New Zealand; The Compass File.

Comments powered by CComment